By the end of my trip in Ulaanbaatar, the weather changed from steady rain to an intense, dry heat. Throughout this experience, I had an amazing group of 4H volunteers along with Binderya (my superstar project assistant) surveying ger district residents for the Nomadic Mapping Collective. Long days of sun and hot weather were no deterrent, and many of the ger district residents offered tea, candy, and respite. It was the complete opposite of a visit from Comcast, and it took me awhile to adjust to this overwhelming hospitality from the residents. I originally imagined a string of visits in one day, showing up to a hasha (the household yard), going through all the measurements, and leaving. This vision of "get-it-done" home visits did not come to fruition, yet the reality became a welcome detour -- I learned a lot from talking with the members of each household. By the end, we started shortening the name of the Nomadic Mapping Collective to just “Mapping Collective” -- the nomadic part was blatently obvious to all involved.

Our collective led a user-centered design process that I never had imagined we could accomplish (language barrier being one obstacle!). Over 100 interviews and paper surveys were gathered from three distinct districts in Ulaanbaatar -- Songino Khairkhan (one of the poorest ger districts by income level), Chingeltei, and Sukhbaatar (one of the older, most established ger districts).

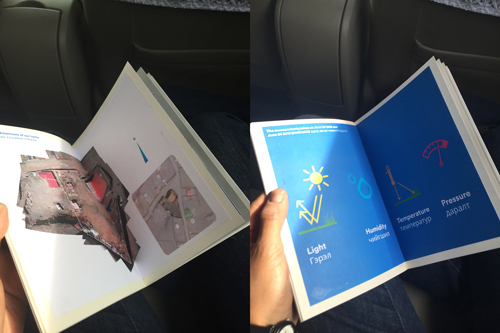

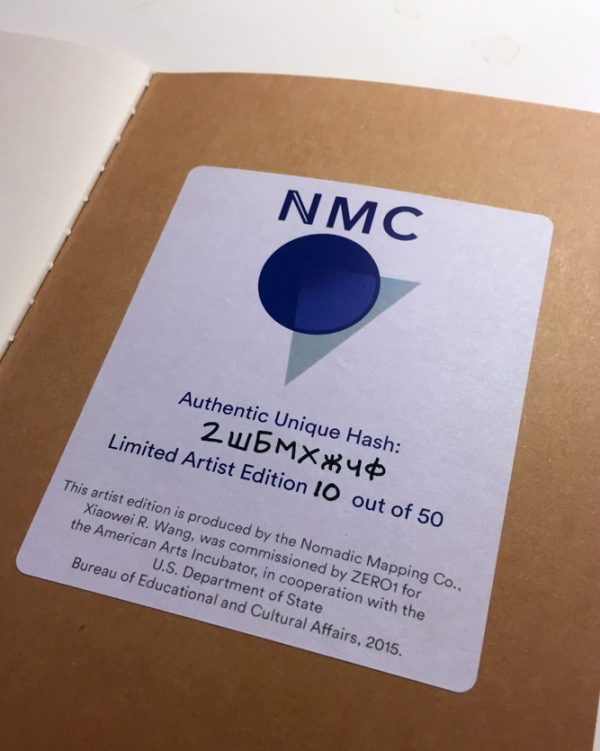

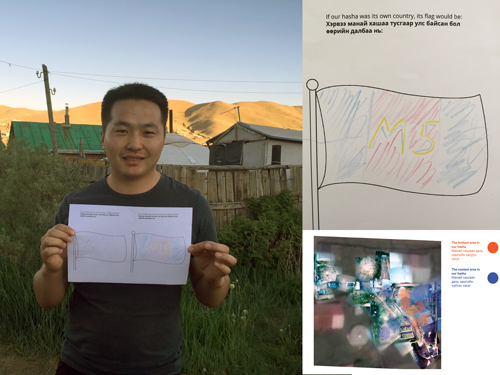

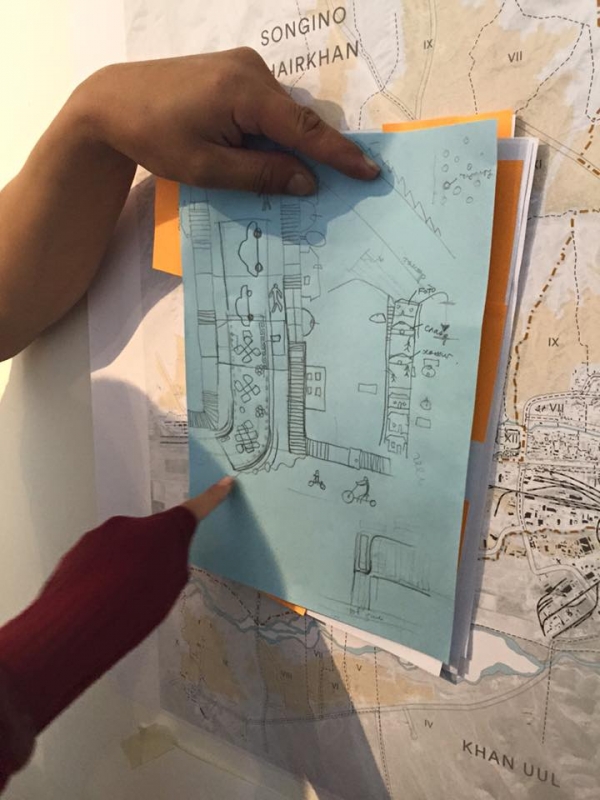

We ended up doing detailed site surveys of 15 hashas, or yards, and making these into artist edition booklets. These artist edition booklets were a collaborative effort by the Mapping Collective and the members of each household we surveyed, and were given to each hasha household for them to keep. It wasn’t an official legal document (although I did try to convince Binderya that a public notary should stamp our editions -- she insisted that it would have been near impossible), which is why we referred to it as an artist edition. Still, these printed documents were a way to empower residents with actionable data for designing their yards, and to allow ownership of their own data.

We were tackling two issues with our artist editions -- (1) the misconception that ger districts, as informal spaces, were full of shoddy, haphazard, non-data driven planning / construction by residents, and (2) the common practice of ger district data being collected by many government organizations, foreign aid orgs, and other NGOs but not shared with the residents being surveyed. From the beginning, this lack of data accessibility was a sore point amongst many ger residents. Being excluded from the data led many residents to be suspicious of the data collection processes, and limited the number of residents willing to participate. Instead of being privy to the survey results and thus empowered to change their environments based on the data, residents watched data flow to "outsiders" who designed and planned the ger districts. The Mapping Collective’s artist edition sought to change this by collecting and sharing actionable data that supported residents to make decisions (e.g., where best to put a small garden or a greenhouse). Also, we hope these artist editions will be considered under intellectual property law, and that the data will hold legal gravity as a work by the hasha residents that could not be taken or copied without their permission.

Referencing legal / contractual art such as the work of Superflex (http://superflex.net/tools), when a resident agreeds to have his/her hasha surveyed, the resident becomes part of the Mapping Collective. Because the Mapping Collective owns the intellectual property of each artist edition, the resident thereby becomes "owner" of this artistic representation of real data.

We built into this artist edition analysis of the hasha characteristics like hottest place, coldest place, most humid place, best places for planting, etc. By including this analysis, we transformed the idea of data-driven design in informal settlements into reality. Many of the residents expressed interest and excitement in interviews and paper surveys about improving their hashas -- which proved right our hypothesis that ideas of “run down ger districts where no one cares about their environments” were simply a false construct. Most of our survey respondents chose to live in ger districts because it offered them the open space to have at least some sort of nature or connection to the landscape in a way that apartment house living did not.

Finally each artist edition was given a special hashid in Cyrillic as a mark of authenticity -- there now exists a list of official, Mapping Collective-recognized hashids.

This unique hashid provides access to each hasha owner’s data online, in a private way, almost like a data locker. Residents will be able to access their data via nomadicmapping.org by entering their hashid (which was done in Cyrillic, to accomodate Cyrillic keyboards). Having some data online made sense, as there were a lot of measurements, calculations, and analysis that went into each hasha -- we couldn’t fit all of the data into one printed booklet!

When I began this project, I thought that the Mapping Collective could corral the data simply through open-source collection methods. Yet through extensive surveys and face-to-face conversations, it became clear that data ownership and control over channels of distribution were extremely important in Ulaanbaatar, almost culturally antithetical to certain Californian ideals of open sourcing everything.

As we discussed this project with participants, a lot of them actually brought up the incident of Google Maps in Japan, where privacy was a major concern (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Street_View_privacy_concerns). It was here that I learned a lesson: while in certain pockets of the West we love and exoticize open data and public data, it’s not true everywhere. In fact, in at least half the world, the idea of putting all your home’s data online is a violation in so many ways - why do it? One resident even brought up the weirdness of Google Maps and that maybe the idea of “public” data was just a ploy for Google to gather information about people without seeming too sinister. This expressed need from residents to keep their data private and truly have ownership of it reaffirmed our format for the artist editions, and emphasized the Mapping Collective’s belief in empowering the ger district residents through actionable data.

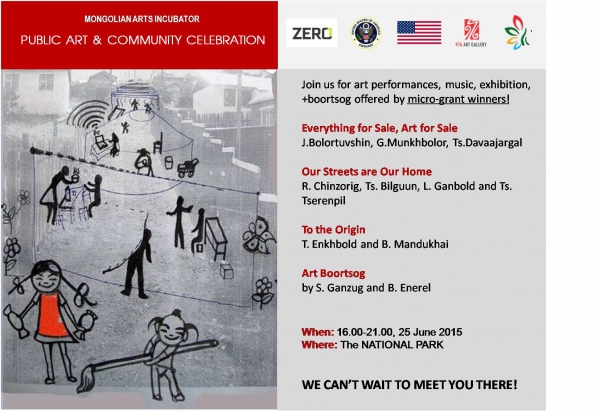

Meanwhile, while conducting ger district surveys, we also were organizing the final community event, to be held at a beautiful Ulaanbaatar park. All four projects had either begun or were nearing completion.

The Art Boortsog team (http://youtu.be/PsOS2QtWx7k ) had been going out every day, to some incredible places in Ulaanbaatar that no one would think to go -- everywhere from ger districts to sites of extreme poverty. For project creators Ganzug and Enerel, it was an up and down that brought some invaluable food for mind and body to marginalized communities, but also made them confront aspects of their practice in new ways. During the final event at UB Park, they showed images from their project and made Boortsog.

Our Street is Our Home created a set of gates for their installation at the final event -- bringing the atmosphere of the ger districts to the center of the city. They hung specially made curtains that usually line the inside of a ger (yurt) into gates, making a public place a "home" for dialogue. They plan on turning their recent installation event in the ger district last week into a more regular occurrence, almost like a public art event, beginning again after the July Naadam holidays.

To the Origin arrived back from their long nomadic journey. They showcased their work, their variation on a ger (yurt), and did a performance that collected the works they showed in the countryside, transposing it back onto the Ulaanbaatar city fabric. “If you can understand this performance, you can probably understand most things about nomadic life," explained the project leader. They will continue working on the documentation and digital components.

Everything For Sale showed the results of their initial work -- selling fresh air, animal bones, and CDs with the sound of “silence” at one of Ulaanbaatar’s most famous black markets -- Narantuul. They created print material to promote the “store” and will continue selling their work and talking about different types of pollution with the public. During their black market sale, someone bought a bag of air and sucked it down in one go, which says a lot about the state of air pollution and how the public understand it in Ulaanbaatar.

After the public event we spent several days compiling the artist editions for the hasha surveys, delivering them, and collecting feedback on them from the new Mapping Collective members.

The mapping and workshop materials now belong to the Mapping Collective of Ulaanbaatar -- a diverse group of middle-aged ger district residents and 4H volunteers. All equipment will be part of the American Corner makerspace, at the Ulaanbaatar Public Library. The American Corner is a public space inside the Ulaanbaatar Public Library, maintained by the local U.S. Embassy and common in a lot of countries, that provides resources and programming. We held talks at the Ulaanbaatar American Corner, and 4H has been using the American Corner for education and workshops for the past 2 years.

Binderya will lead and coordinate new and continued site surveys as part of the 4H programming in the fall, and I will be supporting her remotely with curriculum ideas. While I can't be there, I know the project is in good hands, and in many ways I'm surprised and deeply satisfied that it feels like just the beginning of a much bigger project.

After all this work, I was heading home to the U.S. and everyone else was off to Naadam celebration and adventures. But before heading out there was one very important thing that needed to get done: take our amazing volunteers out bowling!

It’s been a whirlwind these past few days in Ulaanbaatar. The micro-grant projects are underway, and some of them have been enormously successful already.

Ger districts are called so because they usually have a ger (traditional Mongolian tent) inside a yard. They are “where more than half of the capital’s residents live without access to basic public services like water, sewage systems, and central heating...population growth in the capital [of Ulaanbaatar] is expected to continue at the same pace, and with little affordable housing available, most of the newcomers ultimately settle in the ger areas.” (Asia Foundation, http://asiafoundation.org/in-asia/2013/10/23/mapping-ulaanbaatars-ger-districts/).

This past Saturday I visited Our Streets are Our Home in the ger district of Chingeltei #12. The typical street of a ger district -- dusty, rocky, strewn with debris and bare under the hot sun was transformed. By blocking off cars for the day from the road and transforming the fences and street through a floating ger, painted murals on fences and fabric, the neighborhood became less like a place where people throw rocks at you because you’re a stranger (what happened on my first visit), and instead the good parts of living in a ger district was shown -- community, closeness to neighbors and civic spirit.

I had enormous fun visiting the installation. In the middle of the street was a ger structure suspended over fences. Inside, one of the artists, Narbaysgalan made a brain sculpture for residents of the community to cast their suggestion for neighborhood improvements. It was exciting to see this new kind of art as civic engagement happening in Ulaanbaatar, but especially the ger districts of all places! Earlier, one of the artists, Chinzorig actually invited the administrators of the district to attend the interactive installation, presenting it to them as a future strategy that the neighborhood could do on a larger scale, to really improve civic life from the ground up.

Other projects, like Art Boortsog have also been providing sustenance for the mind and body across town. Residents in ger districts as well as Tsagaan Davaa, an area near UB’s landfill were treated to conversation on art and boortsog biscuits in whichever shape they requested. Even the police were supporting the public art project, while just a few years ago, according to artist Ganzug, the police were the very source of anti-public art sentiment!

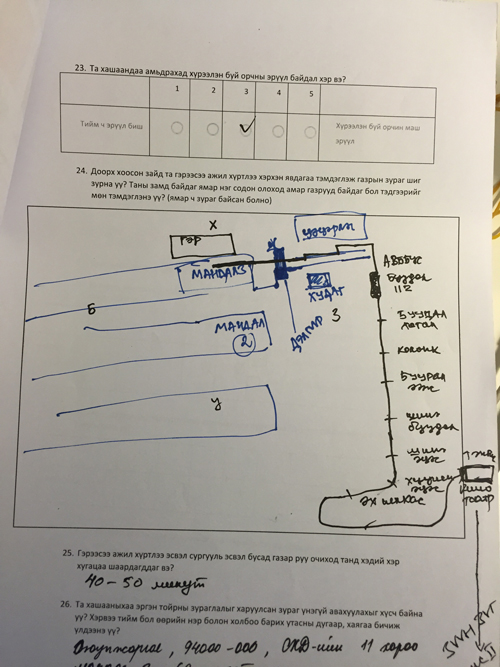

In the meantime, the Mapping Collective has been hard at work, surveying and going to two ger districts -- Songino Khairkhan (one of the poorest and most sprawling) and Chingeltei. We’ve been collecting data to empower people for actionable design of their own hashas (yards), and some high res aerial imagery.

The 4H volunteers of Ulaanbaatar have been an immense help throughout the entire survey process and will be carrying on the torch of the Mapping Collective, using the sensors and other equipment brought from the US. Part of the process has also included on site interviews with ger district households to collaboratively design their artist-edition-data-books. These data books are filled with data about their hashas and the aerial imagery, allowing residents to challenge the traditional notion that those in informal settlements just build haphazardly -- instead giving residents access to the tools for more data driven design. Additionally, it’s no surprise that geographic data, which is extremely valuable for us in the US, is collected and taken by a coterie of organizations and foreign aid in the ger districts but never made accessible again to the residents who were surveyed.

Needless to say, it’s been an incredible whirlwind. Amongst all this we’re getting ready for the final event on the 25th...

After a week of learning new skills, brainstorming, and working together on their presentations, pitch day arrived! There were a wide range of projects, ranging from new media (video and social media narrative to create a fictional scenario and product for one project) to performance art using food, to creating an interactive map showing public art around the city, to interactive art using lights and sensors, and nomadic works bound by the thread of geolocative technologies, maps and tradition. Originally 14 group projects after day 3 of the workshop, some groups and individuals combined to become 11 groups pitching to a panel.

The panelists for the evening were: Shannon Moore, Nathan Johnson and Dondog Badamsambuu from the U.S. Embassy, Solongo Tseekhuu from the Union of Mongolian Artists, and Gantuya Badamgarav from our partner gallery, 976. It was a tough deliberation process, and Gantuya commented that the amount of time we spent deliberating winners was the same amount of time she spent this past year deliberating on Fulbright winners!

From 11 group projects, we managed to select four winners:

Everything for Sale, Art for Sale, by the group Brothers and Sisters, will “sell” three things on a mobile cart throughout Ulaanbaatar -- fresh air collected from the countryside into bags, the sound of silence on CDs, and livestock bones, which will address the different types of pollution in the city.

Our Streets are Our Home, with lead artist R. Chinzorig and group members Ts. Bilguun, L. Ganbold and Ts. Tserenpil will create a one day happening on their street, located in the Ger District where one of the artists resides. Curtains will be hung with color houses painted on them, and wire sculptures of gers will hang from utility poles, creating an environment for interactive art and services from their local neighborhood such as hairdressing, wifi station, tea drinking and childrens’ mural painting.

To The Origin, with T. Enkhbold and B. Mandukhai, where they will travel in the city to the countryside, living in a ger alongside a herder family. They will bring a nomadic exhibition to countryside families and mark points along the way using geolocation, confronting ideas of distance, changing tradition and changing lifestyles.

Art Boortsog, by S. Ganzug and B. Enerel. Art Boortsog will travel to three different locations in Ulaanbaatar -- to a landfill site where families live, to a ger district, and to the center of the city. Ganzug and Enerel will make traditional Mongolian biscuits in whatever shape people at the site request. While they are making these biscuits, they will engage with people on conversations in art, sustainability, hunger and economic conditions. Feeding the stomach and feeding the mind is their project goal.

A huge thanks to all the participants and panelists…it was amazing to have so many good projects in competition with each other. Excited to see what emerges from the micro-grant projects!

Hello, sain bainuu! Or, Сайн байна уу if we’re being proper about our script usage. Like a lot of Soviet influenced countries, Mongolia uses Cyrillic script to phonetically spell out the language. The change in language, weather and time zone makes Mongolia feel like polar opposites with San Francisco. Even though I haven’t been in Mongolia for a full week yet, the whole immersive process into Ulaanbaatar makes me feel like I’ve been here for as long as I can remember. I've been receiving so much since my arrival -- kindness, the great energy of the participants, knowledge and warmth from the host gallery and Embassy here.

I arrived into the tiny Chinggis Khaan International airport late at night, greeted by Binderya Munkhbat, the translator who would be helping me these next few weeks of work. Bindey’s big, radiant smile immediately reassured me that I was in good hands, and that I had an ally in navigating a place that some folks, like the Economist deem “the Bangkok of the Steppe”. (http://www.economist.com/node/21543113). The Economist article gives a pretty good description of UB, although mining contracts have been fluctuating recently. UB is a place where you might think how impossible it is to cross the street with relentless drivers on the road, admire crumbling Soviet style buildings, as you’re on your way to a restaurant with some of the most delicious North Indian food you’ve ever had, run by expats of Hazara ethnicity and eat this food sitting inside a Haveli made of teak wood.

Needless to say, cognitive dissonance is an understatement in UB.

I gave two artist talks the next day, on June 5th to help promote the workshop, one at the American Corner (a program that I was unaware of, but in some cities abroad the U.S. Embassy sets aside a space for learning about American culture) and another at the partner gallery, 976. Right before my first talk, it started torrential downpouring, with pools of water forming in the streets, and I was convinced no one would come to the talks. Bindey assured me not to worry, and that the rain was a good sign. She told me that there is a Mongolian belief that the person who brings the rain, brings good will. People did end up attending and I had my fingers crossed that the same would happen for the next day, workshop day 1.

About 17 people from all walks of life showed up to workshop day 1 on Saturday, June 6. It was a strange day to hold a workshop: I didn’t know that it was Ulaanbaatar International Marathon until I stepped outside of my apartment and the streets were entirely free of cars. Police and barriers were up on the street near 976 Gallery where the workshops were being held. The entire city was car free for the day. Despite the transportation difficulties (no motor vehicles on the roads), we had fantastic energy on the first day. We looked at mapping and cartography as a tool and as an art form itself. Participants then worked in groups to pick a place in the city, went for a walk, and mapped one built or environmental process that they saw. One group managed to map 502 trees in the central UB area! Others went to interstitial spaces near the river, and for one participant who lived in a ger district (http://thediplomat.com/2014/03/mongolia-puts-ger-shantytowns-on-the-map/ for an explanation of ger districts, they are essentially informal areas where traditional felt tents, or gers are set up by families and they become urban campers) it was her first time placing the context of her neighborhood in the larger map of UB. It was wonderful to see how flexible everyone was -- that any original expectations of what an “art workshop” would be like went beyond the confines of traditional artistic mediums.

We gathered more and more new participants for Sunday, day 2 of the workshop. We talked about findings from day 1, and looked at prototyping, making small models, and using LittleBits as a prototyping tool to make interactive sculptures that respond to sound, motion and light. Using these tools, participants were encouraged to take their findings and environmental issue from the first day and connect it to site conditions, socio-economic conditions and put together a prototype. The group that mapped trees the previous day began to refine their idea into a project -- perhaps putting sensors in the soil and lights in the tree that would call attention to issues of soil pollution and street trees. One artist brought his daughter for the day, and they built a sound triggered sculpture together. Another group thought about the countryside, and a way to protect herders’ sheep on the grassland from wolves : if one actuator could trigger a mechanism to wake up guard dogs. It was exciting to see everyone work collaboratively and in such a hands on way -- something is apparently pretty rare for typical, stiff “training sessions” as it’s called here.

We gathered even more steam and more participants on Day 3 -- by then the gallery space was probably at capacity! Nearly 30 people showed up for the workshop, and people formed groups for projects, presented their project ideas and we held some very Silicon Valley style, rapid ideation exercises. We went through what their project idea was, trying to summarize succinctly, plan out a project with budget and go through an impact versus effort analysis to identify where the passion was for each project, what the most important elements were for each idea, and trying to cut away excess elements for increased project agility and to strengthen project feasibility given fiscal and time constraints. I was incredibly excited in seeing the discoveries that people made, and seeing the groups work through a process that everyone expressed was “very, very new” to them.

By the end of the day we had a set of groups with incredibly strong project ideas. Some of these ideas:

-Making a sculpture from dough, cooking it, bringing it to both a landfill site where families in poverty lived, having people eat the sculpture and break bread together.

-Constructing an “art ger” (ger is tent, so it’s a art tent) that would travel from city to countryside, with art workers living inside the ger and offering art beautification services to countryside and city families.

-Taking air from the countryside, putting it into bags, and selling it on a mobile cart throughout the city to raise awareness about the air pollution

-Using environmental sensors to bring attention to trees, through a responsive lighting system

-Creating more trash cans that feature art and eye catching photography in ger districts, as a way of combating litter (since trash pickup is impossible when the trash is dispersed all over)

-Projecting poems outside

-Augmented reality for UB to emphasize history of certain buildings

-Ger district art improvements -- improving an earth road in a ger district by formalizing and building a concrete portion 10 meters long on a key incline, painting the road with traditional, colorful patterns. Also creating curtains to hang over the wooden fences that have become typical and visually representative of ger districts (and thereby equated as “rundown”), with the image of the house that each household would like to live in.

Just some group ideas…! Each group will be working on their presentation in the meantime… !

It’s hard to believe that a year ago I was just beginning to think about a project in Mongolia. There’s a lot of built up anticipation in these next two weeks before I leave, much of it to do with my long-standing interest in Mongolia…

Coming from regional planning, I became fascinated with Mongolia because of its outward contradictions: a highly-networked yet nomadic society, its informal urban planning, its status as a developing country yet without some of what you might see/imagine as a “developing” country. The complexities of urbanism in Mongolia were what fascinated me most: the physical spaces carved out are as much the result of larger environmental and economic systems as they are historic and ideological ones.

What this boils down to is the compelling and somewhat daunting project I plan to develop in Mongolia: The Nomadic Mapping Collective. The challenges that face Ulaan Baatar, Mongolia are not necessarily unique, and in many ways are endemic to many “remote” places. Remote places are rendered remote either by physical inaccessibility, or ever increasingly by the virtual inaccessibility of being "off" the map.

Looking at the Nepal earthquakes and the rush towards virtual mapping as a means to affect physical relief efforts is a reminder – the impactful actionability of data. So much now depends on a map as instructions. Not a set of neutral data, but the instructions and the platform that drives physical actions, the articulation of space. One of the guiding thoughts behind the Nomadic Mapping Collective is less a virtual scan, remotely, but performing "ground truthing" – having citizens of a place articulate their city. "In a classic work, The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch taught us that the alienated city is above all a space in which peole are unable to map (in their minds) either their own positions or the ubran totality in which they find themselves..." writes Frederic Jameson.

So, in a place like Ulaan Baatar, there is much to be learned about maps, about data, about power and logistics. About the forces of development and control that often play at odds with local culture or even preservation. About power and who owns the data, who maps, who has access to knowledge and high resolution digital imagery. About land ownership and documentation.

Or, in the words of the incomparable Etel Adnan: "A map is not about places but about direction. It is to take you to places. It is a dynamic circus. I just wanted to emphasize the nomadic quality of the map."

In these next few weeks, I’m excited for the formation of The Nomadic Mapping Collective, and for the Collective to explore map-making as a tool of social and technological entrepreneurship. Inspired by art as service and forms of contracts as art, the rules of the collective range from offering “paid” services that are paid with using labor, and using the preciousness of limited artist editions (signed, sealed) as documentation for land registration.

There’s a lot of work to be done, and a lot of material to cover. I’ve been carefully going through equipment and testing out some tools, ranging from basic environmental sensors to nifty little drones that capture video. I’m also printing maps for the workshop, making booklets and preparing the artists editions, and preparing for participants to be tour guides. Hopefully as you follow along in this blog, you’ll be able to see the incredible city of UB in virtual space for yourself.

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.19.6" custom_margin="0px||" custom_padding="0px||"][et_pb_row admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.0.74" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

San Jose is a great place. I've been living in the Bay Area since February and I've made it down to San Jose, California only once previously, for the ZERO1 LAST Festival. Prior to moving to the Bay Area, I was living on the East Coast, where cities are denser and there seems to be an inter-city hierarchy where smaller cities cluster outside of big cities an hour or two away.

San Jose, on the other hand, is a huge city with a lot to offer, perhaps rivaling Oakland or San Francisco in its own right. The art-tech scene is fueled by a lot of Silicon Valley spillover and it's really a refreshing and inspirational environment. During one of our evening walks, we passed Jim Conti's Show Your Stripes, a light sculpture on the facade of a building that was programmable by cellphones, and I realized it's pretty special and quite rare to see a public art installation of that size supported by the city and developers in the public sphere.

It was exciting to be there for the American Arts Incubator Orientation, and after several months of correspondence, to finally meet the folks at ZERO1 and Michele Peregrin from the US Department of State in person.

While in San Jose, we did all the orientation activities you might expect: a speed walking competition break, learned more about our roles as artists in the program, and raised and probed into the many questions that would be facing us along the way.

One of the main questions that came up was the embeddedness of us as American artists, sent to a country as vehicles of cultural diplomacy. It reminded me of many conversations on anthropological fieldwork, and a lot of thoughts that surround artistic practice which has to negotiate the notion of “the Other” while being an outsider. In the context of the AAI program, the duration of the overseas trip is so short and an incredible whirlwind, so the issues of embeddedness are really important: How do we make successful projects without seeming like we're swooping in all of a sudden? In 4 weeks time, we will arrive in a different country, hold a one-week workshop, and have 3 weeks to deploy a project. It's difficult enough to plan a project in the US where I know places to get materials, can speak the same language, and can follow up on the afterlife of a project, let alone in Mongolia.

Sustainability of the projects also seemed to be a key issue for all of us artists. We're optimistic that once we are on the ground, we will build enough community and lasting connections that will help maintain the projects, especially if they are more about intangible products – from art as a new kind of commerce to knowledge production.

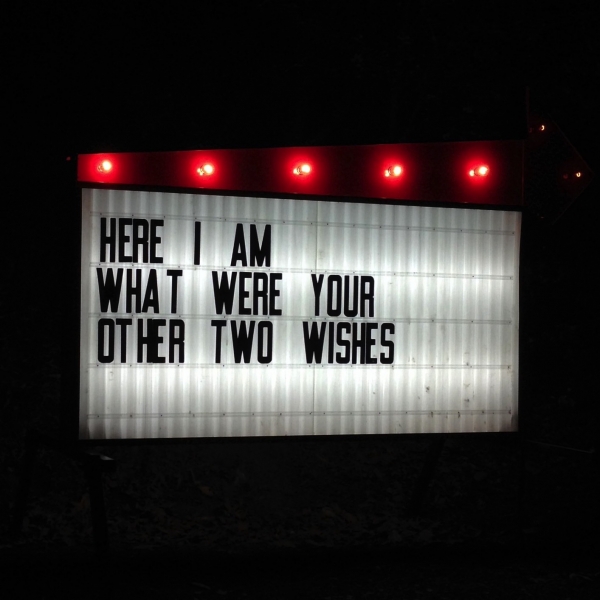

During orientation, we were also lucky enough to head to Montalvo and have dinner with some of the artists in residence there. We saw artist in residence Justin Lowman working on his light installation, and he kindly explained to us the story of the Winchester House that was nearby. We also saw a great installation from Allison Wiese exploring the use of pick up lines.

After a week of discussion, exploration, and play, I headed back to the Bay Area, not without stopping by the Computer History Museum in Mountain View first. The contents of the museum were fascinating, exciting, and brutalist. It was interesting to see the trajectory of computing from visceral, mechanical machines all the way to large black boxes sitting behind glass windows. It made me reflect not only on how the aesthetics of computing had changed, but also how the sociocultural relationships to computing had changed, and were physically imparted onto the tools themselves. The physical objects also reflected the broader industries at play, economic shifts and kinds of labor -- all thoughts that continue to spin around as I work through my project proposal for Mongolia.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

“Why Mongolia?” Zaya asks me, as we walk through patches of evergreen trees, near the ruins of a Buddhist monastery on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar.

In many ways it's obvious, why Mongolia might be the perfect place for a designer to work at the intersection of art, design and technology with a community focus. It's a country full of contradictions with a rich cultural legacy, and the growing pains it faces are extraordinarily complex, especially when confronted with its past.

Mongolia might present images in people's minds of Genghis Khan, fierce warriors or nomadic herders, but the place it is today has incredible nuance. Deemed a “middle income” country by the World Bank, it is also a so-called "developing country", one that faces the resource curse – with billions of dollars of untapped mineral wealth all the while navigating a democratic government that has been in place since the 1990s and the environmental impacts of mining that severely affect the country's other major industry: nomadic pastoralism.

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia's capital embodies many of these contradictions. On my visit, Beijing Street was entirely under construction, leaving residents to walk alongside tractors and construction equipment. In the city center, a Louis Vuitton and luxury hotel loomed large. I was also fortunate enough to see the work of Les Joynes during my visit, who collaborated with Mohanik and local Mongolian artists to create a performance at the Zanazabar Art Museum, replete with a ger or circular yurt structure located inside the museum and combination of old, new, and extremely contemporary art. Meanwhile, the fall air was already smoggy and polluted from the power plants put in by the Soviets and the small household, coal-burning stoves being used in the ger districts.

Before the democratic revolution in the 1990s, during the last days of Soviet influence, only 26.8 percent of Mongolia's population lived in Ulaanbaatar; by 2010, 45 percent of the country's population lived in UB according to the Asia Foundation. Out of this figure, more than half of the city lives in ger districts, areas that have been described by a few organizations as “shantytowns” or “slums”. Many of the districts lack access to essential public services. However, unlike slums, by Mongolian land law, the ger district residents own the land that they have claimed, leaving the Ulaanbaatar city government to negotiate with each household on relocation on a case-by-case basis.

Yet on this day, in the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar, the skies are clear and we are away from UB's incessant honking, traffic, coal-burning and exhaust fumes. There are few sounds of airplanes overhead and it is so quiet that you can hear a wall of wind crash through patches of evergreen trees. Vultures circle the top of the mountain, surrounding a dead animal somewhere in the rocks.

I'm with Zaya, a young video artist who lives in Ulaanbaatar and whose husband's work is up at 976 Gallery, the partner organization for the American Arts Incubator project. We are about an hour outside of Ulaanbaatar, having made it to the ruins despite a major road closure. Instead we drove as cars and shipping trucks have clearly driven for many times before – on bumping informal roads that crisscross the grassland.

The monastery itself is a reminder of all the intricacies that are part of Mongolian history – formerly home to llamas and monks, the monastery was destroyed in the 1930's as part of the Soviet purges on religion and the ruins are now preserved with a tourist ger camp at the foot of the hill. Two Americans pass us on dirt bikes during our visit, careening down the hill with athletic aplomb.

As I've learned, it is more difficult to answer questions that one innately knows the answer to, rather than the questions based on pure rationalization. The question of “Why Mongolia?” can only be answered and understood upon being there and engaging all five senses fully. To understand, one must be there.

Fortunately, I was allowed a few days reentry into this question, meeting with folks at the US Embassy in Mongolia and the partner organization at 976 Gallery. Much of it was a whirlwind but what made the trip markedly exciting was everything the meetings and conversations with people reiterated – for all the promises of technological advancement or innovative futures, the platforms and websites that would revolutionize our world, what transcended words and boundaries were still the very social networks and ties created by culture, imagination and arts. A better question may be, what marks a culture and what shapes a culture?

Statistics & more information on ger districts:

http://asiafoundation.org/in-asia/2013/10/23/mapping-ulaanbaatars-ger-districts/

http://thediplomat.com/2014/03/mongolia-puts-ger-shantytowns-on-the-map/