The Protected Land

Jack is a big dude and an equally big nerd for nature. The man is a machine-gun rattling off bullets of knowledge about everything he sees. “This bird is named Coleto, it eats insects, and has a white patch on its head- that’s why in Filipino we can call the bald people, "Hey Coleto!"

“This flower stays in bloom for six months.”

“This lake turned purple once a couple years ago because of the volcanic activity. They were worried it might release poison gas and kill everyone like at a lake that turned purple in another country.”

Jack is taking us on a scouting trip with Pong, our coordinator from the US Embassy. We are searching for places to build a new Art and Technology Laboratory with a focus on environmental health. He took us to a new nature preserve in a spellbinding site. Two 'twin-lakes' nestled against each other, perched atop a volcano, and surrounded by lush forest.

“The lake on the left of the ridge is actually 10 meters higher than the other next to it, so we know there is no hole in this narrow ridge dividing them.”

This amazing spot blew up 10,000 years ago. Its deep dark craters filled in with fresh water. The volcanic mound was overtaken by thick forest. Only about 10 years ago, the site was officially protected.

“It’s now illegal to pick even a single flower.”

Tree Poachers

On the drive up the mountain, we pass through fancy new real-estate developments owned by the rich, or foreigners, or just those aiming to cash in on future eco-tourism in this developing spot.

We come to a dead stop every fifty feet or so. When we met Jack at the tourism office, he laughed with us saying that if he had gone out with us, he would guarantee that we see at least 30 birds that we had never seen in our entire life (“lifers”). It turns out he was 100% serious about this. As soon as he got in the car that afternoon he said, “I thought we would be leaving much earlier… this changes my guarantee, but I think we will still get 30.” He uses his uncannily sharp eyes to pick out and identify birds on distant branches and trees. He can ID them based on just the subtlest of features. The technical birding term for this is 'jizz' (No, seriously, check Wikipedia). He gets the driver to constantly stop the car on our way up the mountain and slowly creep up on our prey.

We sneak out of the car over and over again as he guides our vision with a high-powered green laser-pen. The birds are true lifers for both of us with the Embassy. Strange features, long tails, bright gaudy colors, weird songs. Looking past the birds though, one starts noticing a pattern in the distance. Featureless bald patches infecting the mountain like a flea-ridden dog. While the volcano we're heading towards and the thin strip of road leading up to it are lush and green, the surrounding forest seem mangy. Tree poachers.

“There is a bird that is supposed to be extinct here on Negros Island, but I have seen this bird three times.”

Jack explains, “After the first two sightings, I got a cameraman to find it and get good proof with me.” We climbed up the ridge over there. Got up early, some coffee, some bread. Took all morning to get up and we waited. Suddenly we heard a strange sound, and the bird lands right behind me. It’s huge. The camera guy is all surprised and drops his camera. He picks it up to get a picture but then this other sound. CRACK. And a huge rustle of a tree falling down nearby scares it off. Tree poachers."

It’s hard to tell where they are stealing trees. Jack explains they build cases around their chainsaws which connect to tubes that pass through big drums of water. Chainsaw silencers. That’s how they could be so close to him on the mountain-side and only be detected when the tree actually starts falling.

After missing out on this special bird, Jack went to confront these tree poachers. “I tell them that this is protected land and it’s illegal to cut down trees. Then I notice the two M16’s they have laying out, and I shut up, and just walk away.”

Hemp Poachers

We go down into the crater and hop on a small catamaran. The lake is smooth and peaceful. Floating in the lake we are surrounded by a ring of wild greenery filled with hidden birds. There’s mist moving between nooks in the encompassing mountain, and everything looks like Jurassic Park. Pong and I continue our routine of sitting patiently, admiring the mist moving in and out of the trees and ridges, while Jack scans the sights and sounds for fresh birds.

We pull up to a waterfall and Jack gets excited. There are two shirtless guys working in a clearing right next to the park’s path. “Oh wow, this is very interesting to see, these are hemp-poachers!” Jack invites himself (and us) into their clearing where long silky hairs cover a fallen log. He smiles and gets them to (obligingly) show off the tools of their craft: simple blades embedded in logs, mechanisms for shredding trees into soft fiber.

“They come from about a day’s journey away. They hike here, camp for several days, then bring hundreds of pounds of the fiber to sell in the city. They can get about 10 times as much from this as shredding fiber in other places.” The poachers gave a quick smile pointing to how their tools worked, but their focus immediately returned to their labor. They shredded these trees, feverishly, non-stop. “On a good day, they can make 100 pounds of this material. They can sell it on the market for about 200 pesos.” This is $4 USD.

We keep walking down the path. We see the waterfall. We take pictures of it. It is pretty.

Bird Poachers

Driving back down the mountain, we pass a boy working at the gate. “You see him? His father was just killed by poachers a couple months ago.” Jack’s cheery, fast-paced demeanor drops a bit. “His father saw some people cutting down trees, so he got his radio and reported it. Actually it doesn’t matter if he actually reported it or not. People said he was the one who reported it. Well, one night the poachers came to his house and shot him. Now his son still works here at the park.” We sat and he continued, “You see it makes it very tricky to do this job. We want to protect the park and stop the poachers, but often it is too dangerous to do anything.”

Some moments pass. We were tired from the adventure, and this final story made the sadness of this environmental destruction real. After a bit of quiet traveling, Pong tries to lighten the mood with a question, “When did you become a birder? Have you always just liked birds?” Jack responds, “No, I used to poach them.”

This took us both by surprise. “What?” Pong asks to clarify. “Yeah, I would go out on hunts and kill many of these birds I am showing you…like those hornbills we saw.” “Why wouldn’t you just eat chicken instead of these endangered birds?” she replies, still quite puzzled by this revelation. “Oh, if I found a chicken, I wouldn’t even eat it. I could take that down to the market and sell it! I poached these birds for food. You can’t sell an endangered animal, but you can eat it if that’s all you have.” We sat there shocked for a while. He gave us a short moment for all this to sink in, and then went right ahead, matter-of-factly, into the technology behind such poaching. “You see we could get a small PVC tube, some alcohol, and some marbles for ammo, and then you would have a silent gun for hunting in protected areas.”

NOTE: I take full responsibility for butchering any of the facts, spellings, or parts of the story throughout this essay. My post is written from memory.

***

The writing above was the first journal entry I started writing for this Philippines art and environmental health project. This happened during the initial scouting trip, but it was such a strong experience, it took me time to assemble it coherently. The trip, the poachers, their technology, and Jack. These elements resonated with me during the entire Waterspace project here in the Philippines. People were destroying the reef. People were destroying the beach. People were destroying the mountain. They were coming up with clever ways to do so, and even maintain pride in the sophisticated ways they found to do it.

Jack had 9 children, two with severe cerebral palsy. He only stopped poaching because he was given the opportunity to use his brilliance to help protect the land and get paid for these abilities. He would have no qualms with going back to poaching if that was his only option to feed his family.

And that there is the problem. I used to think poachers were inherently evil people. Captain Planet would go fight piggish-looking villains with simple, deranged motivations like “I WANT TO CHOP DOWN ALL THE TREES!” But these were not villains. They are a result of what happens when we push people to the edges of society. They have to make decisions - choosing themselves or the environment. They aren’t normally destructive or violent unless they are pushed into it. People become animals when we make them that way.

The other problem is that nature dies slowly. The rest of us, having a nice time reaping the spoils of life within society, don’t get immediate feedback from the blight of a clear-cut mountaintop. We can’t feel the infinitesimal rise of the ocean, until it starts surrounding our house 20 years after burning the carbon we released into the atmosphere. Instead, we need to find ways to make people care about natural diversity for its own sake.

So there are two things we need to do:

We can’t just slap down basic rules saying, “Don’t do this. This is protected area,” when there is a much louder voice saying, “Do this, you need money, you need food.” And this louder voice comes from us. It comes from our families needing nourishment. It comes from our communities demanding new consumer goods. It comes from us telling poor people that the reason they are poor is because they are not working hard enough.

We are killing off our own life support system. We need to protect our environment, and the way to do that is to first protect the poor and underserved humans.

I hope the BOAT Lab is able to do this, and can shine a light on these intermeshed economic and environmental problems.

We managed to get the full BOAT Lab built and fully operational in the two short weeks before the big exhibition! To celebrate this achievement, we held a grand gala opening ceremony for the BOAT Lab and all the Waterspace projects.

This new video describes the whole project leading up to the ceremony.

In spite of the fact that high profile national elections were occurring this weekend, we had a huge turnout with representatives from all over the Banilad neighborhood, Dumaguete, the Negros Island, and even an embassy representative from Manila. Marine biologists, artists, engineers, kids, adults, all came together to experience our projects.

We started the day with open tours of the BOAT Lab and demos from all the teams. People got to ride around on the BOAT Lab, see how our different sensors functioned, create useful items out of garbage plastic bottles, and experience a semi-3D fog-projection room.

As the open tours and demos wound down, we moved into the official opening ceremony. We had talks from locals, formally introduced all the projects, and discussed positive actions to promote education and environmental health.

The ceremony closed out with a thrilling (and hilarious) new play from Team Tapok. Their play dramatized local political events in which large companies exploited poor communities to destroy the environment. It resounded deeply with all involved.

And finally, like all Filipino events, I've learned, the party ended with plenty of food!

The teams will continue working throughout the summer (and hopefully over the whole next year) building amazing water displays, environmental sensors, and holding electronics workshops on the ocean. Perhaps the BOAT Lab’s most important role is simply this — facilitating a cool place for folks to learn in direct contact with technology and nature.

Simply put, this is how the whole program works: we try to complete 5 big projects in just 3 weeks!

There’s a main project led by myself as the ZERO1 American Arts Incubator lead artist, which will be the BOAT Lab, a floating art and technology laboratory focusing on improving environmental health.

Our target site for these projects is the beach of the Banilad community. Banilad is a small neighborhood (or, barangay) south of Dumaguete. It generally consists of poorer fisherfolk, who make their livings catching, drying, and selling fish. It is also home to a beautiful coral reef, but (like most reefs in the Pacific now) this natural treasure is on the brink of destruction. In an effort to save this natural resource, it was recently designated a “Marine Protected Area.” The central tenet of the protection is that fisherpeople are no longer allowed to fish within the area because it hurts the reef. There is even a set of guards from the local community who are paid to watch the reef (the “Bantay Dagat” or “Watch the Sea”). At the end of the exchange, we will be turning the BOAT Lab over to these Marine Guards so they can use the floating lab as a guard station.

PROJECTS

BOAT Lab

The BOAT Lab stands for "Building Open Art and Technology." It’s also a boat! This will serve as a sort of community science center. It's a floating raft equipped with all sorts of equipment, not only displaying art and technology, but also allowing people to build it on the spot. It’s a makerspace floating in the sea that also collects data through sensors and robotic submarines. It then serves as a public art display of this data via LED strips that change color and patterns to let the public know and appreciate what is happening in the sea.

The Sea Sense group will develop an automated multi-sensor technology to monitor sea water quality parameters (pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity). A pumping machine will be utilized to extract seawater samples from between 10ft to 15ft depth. The data gathered can be translated into meaningful information for the fishermen to monitor the fish productivity in Banilad Marine Sanctuary. Further, this project is useful for researchers to monitor climate change effects to prepare the community for the potential impacts of climate change.

Sea Sense Team Members:

Team Viz works to interpret the data from the Sea Sense Team's outputs. They're creating a 3D-like projection screen that uses mist/fog (figure 1) to display what’s happening underwater or other relevant videos. The LED strips (figure 2) send information through a series of creative light designs and patterns. This visualization will entice people to get involved and try to make a difference themselves.

Viz Initiative Team Members:

Team TAPOK is a performing arts crew. Their goal is to inject a message of environmentalism and good uses of technology to the public by hosting a series of theatrical plays in Banilad and the surrounding community. Team TAPOK focuses on performing theatrical presentations to spread awareness of what is happening in our society today and how the humankind has greatly affected our only home, the earth, as well as providing necessary informations on how we could cope up with the damages that we humans have injected.

This group is made up of faculty and students of Foundation University. Their project is based on an idea of Dave Hakkens. The group will make machines that shred and turn plastic into other objects. By showing the community the products these machines can make, they will give people another reason to collect their plastic bottles instead of throwing them away.

Meeting with the locals at our site in Banilad, we asked them what the biggest problem was in their area. They unanimously said the same thing: garbage, trash, basura.

Not only is there a lack of trash pickup on land, resulting in discarded bottles everywhere, but trash from up the island accumulates along the ocean's shore. Sadly, the nearby reef can also act as a filter, catching a lot of this garbage. During our scouting snorkeling trips we ran across many examples of this.

The video below discusses just one instance of how nasty some of these problems can get.

The sun goes away here each day in a glorious explosion of colors. The darkness doesn't cause anything to slow down though. The fast-paced Waterspace teams keep on trucking throughout the night. The crew is excitedly tinkering away on a million different little projects.

Here are some examples from just one night:

The performance art team prepping for night rehearsals.

Neil tinkering with LED control libraries to plan out our visualizations.

Andrew hunting down speakers in local shops (so that the BOAT lab can rock out).

Carl and Mein building the case of their own fog machine / video display from scratch.

Testing out the Weather Station.

Calibrating the water quality sensors.

Andrew building his own LIPO battery chargers. After our struggle finding a source of LIPO batteries for the submarine (and building a custom holster for them), we were still only able to find a single charger in town that works for them. So time to hack together our own!

And a bunch more glowing, sizzling, beeping projects all going at once. It was a noisy, fun night, like they all have been. Only a week left until the big reveal!

The workshop phase of the Arts Incubator went into full force this week. The goal was to fill the participants' brains with new ideas, complex issues, practical experience, and technological know-how until their minds were completely blown, then to clean up those mangled brains and distill all those experiences into four projects teams. At the end of the week, we presented all the projects to a community panel including a special guest from the US Embassy in Manila and the President of the Banilad Bantay Dagat (Marine Guardians).

At the beginning of the week, we made some site visits, tested out the first part of the BOAT Lab, and interviewed locals about the issues that matter most to them. Our site location is Banilad, a sleepy little fishing community with a hidden treasure of a coral reef right offshore. We found their biggest concerns were the pollution in the area and how the water quality might affect both the beach and the marine protected area.

Then we came back to our (non-floating) workshop to dive into these ideas and create prototypes.

From this grew four strong teams each addressing an issue of how to combine art, science, and technology to help combat and increase awareness of ecological destruction. I could tell you about each team right now, but it’s been an exhausting week, so you can learn about what each team is going to do in the next post!

In the meantime, here's a great way to immerse yourself in our process. We've been fortunate to have a world-class student documentary team from Foundation University capturing all the amazing work that's being done. Check out some of the videos they have been putting together daily covering our projects:

Once I land in the Philippines (after a 30+ hour series of flights from Atlanta), I have 29 days to fit in as much as I can. So I have to hit the ground running.

Luckily we managed to assemble an awesome team before I left!

Loushan has volunteered as the lead secretary administrator of the whole Waterspace program. This will be particularly useful for me when I am gone. She has been checking in on each of the project groups. She, herself, is from the youth performance group in town, YATTA.

Zorich is leading the Estudio Damgo crew as they assemble the initial pilot raft project that will be used to test out laboratory gear. His target was to have an approximately 4m x 4m raft ready by the time I got back in April, and he totally nailed it! He got together the construction crew and using recycled old parts they put together the first module! We hope to get it on the open ocean any day now.

Zorich and Loushan are also leading the way in constructing the submarine. They are rocking it so hard!

Greyhound studios is Foundation University’s in-house video production group. They are amazing, motivated, and quick. Having created lots of videos about all sorts of topics around the University and Dumaguete they already are on top of how to handle many logistical problems, so they are super helpful in the general production of the program as well. They have a rotating schedule with three helpers documenting each day of the program. I brought some of my own documentation equipment for them to utilize as well.

Carl and I have been diving into the world of programming arduinos and sensors. He already got an ocean wave detecting sensor hooked up to some nice waterproof lights.

He's agreed to lead some workshops training some of the (pro-active and dedicated) Yatta crew-members in weekly workshops until i come back!

Zing put together amazing logos to help the community organize around the big ideas of this program. There are two different logos. There is the BOAT lab (Building Open Art and Technology Lab) logo, which we can use for the physical space and the floating hackerspace we make. It looks like this:

And the other logo is for the entire American Arts Incubator program in Dumaguete:

These logos are a terrific way to share complex ideas with simple graphics that the participants can all rally around. T-shirts are on their way!

This awesome crew made excellent use of the interim time between my scouting trip and the upcoming workshop. Things are just going to keep getting more exciting as we add and expand upon these initial teams.

And last but not least, we have our incredible production assistant, Geline. She’s ready to tackle any problem, and is a vital resource to keeping our whole operation going at full speed!

In March, I had both my first scouting trip for the Arts Incubator as well as my first experience ever with life, culture, and nature in the Philippines, and more specifically, in Dumaguete. As an outsider, I wanted to collect my initial impressions of this fascinating place that soon would be my home. As I venture into the intense experiences living and working in Dumaguete, it is my goal to use these first observations to help process the experience and understand how my own ways of seeing this place will shift and evolve. Sharing these impressions also can help those with whom I will be working and living get an idea of how I am experiencing their world and how that's different from my experiences in other places. Then they'll be able to share contrasting points or different opinions. This post also will reveal how much of a noob I am about Filipino culture and how much more I have to learn!

Of course my initial impressions are generalizations, and there are counter-examples to all of these.

This is a positive stereotype that really rang true. Everywhere I went, Filipinos constantly went out of their way to help me; from the Tokyo-Manila flight attendant giving us a ride to our hotel, to folks walking with me for blocks to show me where to purchase a used bicycle. While walking around in public areas, I did not seem to be put into the “outsider” box, but rather was welcomed. I felt more accepted than other foreign places I have visited.

The town has an unending sea of motorized tricycles flooding its streets. They are loud, smelly, and make walking through town difficult. Moving through the town chokes you with exhaust and deafens you to anything but the busy city. That being said, a 10-minute walk to the edge of town brings you to some of the most beautiful areas I have ever encountered. The city ends abruptly, the trikes quiet, and the fresh air moves in under a clear, starry sky. With the city growing, and major concerns like the energy plant’s developments on Mt. Talinis, though, the peaceful and beautiful parts of this region appear to be losing the battle.

Like this thing... It was beautiful! This whole part of the ocean filled with flags blowing in the wind.

During our initial visits with different groups of artists, activists, engineers, and students, we were blown away by everyone's enthusiasm. Person after person came up to me, spouting all kinds of different ideas that interested them. While I have run many different workshops, the participants here had a different attitude than I have experienced. I would say that one of my roles during a typical workshop in the US is to try to take in a bunch of wild and crazy ideas from a group and help them realize these thoughts with technical skills. In Dumaguete, I almost faced the opposite. The people I met represented a vast wealth of technical, social, and artistic skills. They were sophisticated architects, activity organizers, or meticulous artists. Their questions to me instead were about how to turn these valuable skills into something fun. More than one person asked me “Can you teach me how to be creative?” This is a question I have never been confronted with, and it will pose an interesting challenge for me!

I’m a person with a major sweet tooth. In the US, I go nuts for candy and often finish huge bags of M&M’s before the trailers even finish at a movie theater. Everyone had told me that the Philippines had a big issue with sugar infiltrating all food, but I had not expected what I encountered. Fried and sugared food is ubiquitous in an almost depressing way. For a person who usually craves sugar intensely, I was so inundated with it that I began craving vegetables and leaves! My favorite food became a salad of bland, boiled ferns. The entire town feels like a food desert with only heavily processed cheap “fast food” available. Some folks seem to react to this by aggressively only going for certain types of healthy foods, but most seem accustomed to this style of food. I remember when I tried ordering snacks for a group meetup... I wanted to purchase the most “authentic” pizza I could find, but nobody was happy; apparently the pizza was "too bitter, not sweet enough."

Owing to it's fragmented island nature and waves of imperialism, the Philippines is hands-down the most interesting mash-up of cultures I have been lucky enough to experience. Just in the language, there's a seemless flow between bits of indigenous cultures, nearby islands, Spanish, and English. People's names were one of the biggest displays of this hyper cultural diversity for me. For instance I met amazing folks with names spanning from the super familiar to the incredibly foreign to me. Some examples include names like Mark, Henry, Dan, Humphrey, Zorich, Fry, Apple, Ying, Ritchley, Prexyl, Zing, and Irish (as she introduced herself, "My name is Irish, but i'm actually Flipino). It's an awesome blend of cool names and cool people!

Everyone calls me “Sir Andy.” I’ve never had this honorific before, but it’s pretty fun! I recently earned my PhD, so it’s been fun getting the occasional “Dr. Andy,” but “Sir Andy” is way cooler!

Orientation is fast and crazy.

ZERO1 is a triumph of biting deep into projects and rolling with what you are actually able to accomplish. Big public projects almost always need to play by a certain set of rules. People aren’t going to give you money unless you can scale the ideas way down, have concrete illustrations of each part, and are able to spoon feed tiny ideas to the key players involved.

ZERO1 seems to understand these constraints and provide ways to work around them -- which is awesome.

I have had plenty of proposals rejected for these very reasons. Organizations, especially large bureaucratic orgs, necessarily have difficult times trusting overly-ambitious artists with broad-scoped projects. However, this orientation has introduced me to an organization as fearless and ambitious as I am. Joined with the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, they not only embrace projects which do not limit their scope to simply one area: “art”, “technology,” “science,” “community building,” and “social justice”, but in fact, encourage a hybrid.

Preparing my proposed project, I decided to pitch a massive concept. I am going to build a huge floating hackerspace! It’s going to be 10 meters wide on a side, and stocked with all the essential gear to make a floating laboratory. The key is to be able to have tools for creating and iterating on digital devices for exploring and understanding the aqueous environment in the sea.

I submitted the idea, and waited patiently for the inevitable kickback. I sat for weeks, nervous about the email that would come stating something along the line of “oh… that’s great, but you need to think smaller,” or “perhaps you need to just take one tiny piece of this idea and only go with that.”

But it never came.

And honestly I was confused. I kept talking with more people about it as I arrived, and I only kept getting positive responses and suggestions and improvements. Finally on the day of the actual pitch, the director of ZERO1, Joel Slayton, was the first person to finally call me out.

“You are BUILDING A BOAT, you realize how big this project is, right?”

“Yep.”

“OK, here’s some ways we can get started...”

I’m just starting up a new adventure with art, technology, and the natural environment in the Philippines. It’s a project managed by ZERO1 in partnership with the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs! The goal will be to launch several projects with community members that combine digital technology with local crafts in order to address the issue of Environmental Health.

My previous work (digitalnaturalism.org) has involved working with scientists and crafters to build technology to interact with animals and natural environments. Typically my personal blend of interests and experiences across science, technology, and the arts can make it hard to find programs that support all these realms; this generally means I am forced to downplay some parts of what I do, in order to focus on the specific technological, scientific, or artistic tasks at hand. ZERO1's unique program allows me to explore and protect natural environments via collaborative new media art - a true synthesis of my favorite passions.

Most of my previous work took place in rich tropical environments (such as in Panama and Madagascar) full of unique creatures in special relationships. Being able to continue my work in the tropics of a new fascinating place (I have never been to the Philippines before), increases my exitement for the AAI program yet another level.

Preliminary Research

I am just starting to research the Philippines and specifically Dumaguete, the main town in which I will be based. As I mentioned, I have no firsthand knowledge of the Philippines, and the basic idea of a country formed out of a collection of tropical islands is fascinating.

Dumaguete itself is located several islands south of the largest, and perhaps most well known, city in the Philippines: Manila. The island it is located on is called Negros (“Black Island”), and is divided into east and west provinces. Before the Philippines was colonized, most of the islands were apparently inhabited by different groups of indigenous tribes. On Negros, the indigenous locals are referred to as “Negritos,” and from my early research there looks like a fascinating cultural center nearby in Dumaguete called Sildakang Negros Village. Dumaguete is now known as a small university town hosting Silliman University.

The first thing most discussed when looking into Dumaguete is the broad array of marine resources. It’s seated at the edge of a channel of several islands known to attract sea turtles, dolphins, and whale sharks. Terrestrially, Dumaguete is near a couple national parks home to interesting animals such as Flying Foxes, Hawk-Eagles, Leopard-cats, and Tarsiers. Negros itself is home to most of the endangered species in the Philippines as it is one of the areas most threatened by development and environmental destruction.

Right now I am focusing on making as many contacts as possible with researchers who have worked in the Philippines along with Philippine-run organizations in Dumaguete. It’s thrilling to imagine all the different ways this project can turn out!

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.0.47" custom_padding="0|0px|29.4844px|0px|false|false"][et_pb_row custom_padding="0|0px|14.7344px|0px|false|false" admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.19.6" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

Today is my last day in the Philippines. A few hours ago I landed in Manila, after waiting for over an hour while the Presidential airplane was landing at the Bacolod airport. I was already installed in my airplane seat, all buckled-up, and through the tiny

After all the anticipation, President Benigno Noynoy Aquino III was descending from his airplane and everyone around -even inside my airplane- suddenly stood up while a small marching band played quietly the national anthem in the background. This moment was perhaps the best closure for my time in Bacolod, also the moment when I finally understood something essential about Filipino culture: This is a place bound together by very strong community values. A strong sense of togetherness, a shared identity, and most importantly, an admirable resilience to an adverse history (colonialism, natural disasters, inequality) rule this country. I couldn’t be luckier for the opportunity to work in such an energizing context like Bacolod City, where art and community engagement come hand-in-hand.

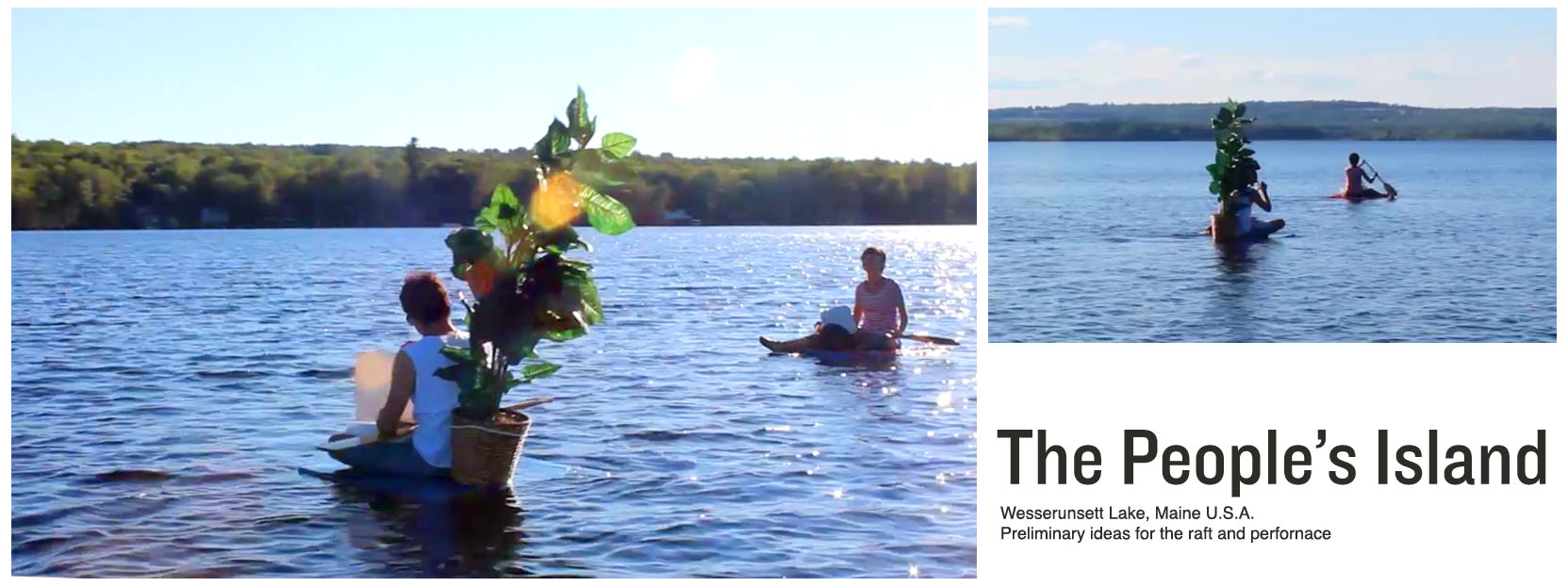

Shortly after I landed in Manila, I had a three-hour taxi ride through the city’s heavy traffic, even though I was traveling only 7 miles. I was heading to Green Papaya Projects, a well established independent art space that has been active for over a decade and run by amazing people (Pewee and Merv). They had invited me to give an informal presentation about my recent work in Bacolod and “The People’s Island” project. You can imagine, I was both excited to share the experience and very fresh documentation but also quite nervous since it was only five days after the public launching of the project and I was still processing the intense experience...

So, after a public lecture at the Negros Museum addressing the role of Public Art in fostering community participation and healthy environments; a five-day workshop exploring collaboration; sustainable urban planning and socially engaged art, I invited participants to creatively explore their city as an extension of the endangered natural world. This is how The People’s Island became a thinking tool, a collective dream and an immersive artistic experience that engaged around 150 people through a public event and exhibition.

Framed as a large participatory art project, The People’s Island really took place in the public sphere of Bacolod: in urban spaces, natural sites and even in our collective consciousness. The project evolved slowly during three weeks of intense work, conversations

Thus, on April 25th at

Once the public arrived

Around

Around

Around

*Its next destination will be Suyac Island in the Northern part of the Negros region, where the structure will re-emerge as the Floating Eco-Resource Center and Library.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.0.47" custom_padding="0|0px|29.4844px|0px|false|false"][et_pb_row admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.19.6" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

It’s a hot Saturday afternoon and I feel my voice resonate strongly inside my chest while my hearing still recovers from the pressurized cabin of the airplane. I can even hear an echo leaking through the century-old walls of the Negros Museum in Bacolod… Well, the fact is that I’m

This was just our third day in the city and my brain was already full of ideas, questions, and yes, lots and LOTS of new names to remember. Just the night before, I gave a public lecture in the same room, which created a lot of curiosity among local artists, environmentalists

During the same talk, I introduced the public art project that I will develop in Bacolod titled, The People’s Island, which revolves around the idea that “reality is none other but the things we do together.” On the one hand, The People’s Island is a metaphorical site, or perhaps a thinking tool that allows workshop participants to create a fictional place that responds to their visions of what their ideal city or environment could look like. Throughout the workshops, participants gathered their concerns about environmental health and re-enacted them through quick, stop-motion animations. They then designed 3D scaled models of a fictive city, as a means to propose sustainable urban planning. This was achieved by transforming small paper sculptures into plans for hybrid objects that use clean energy and have a public function—from street planters that collect solar energy and emit light at night that replace expensive street lighting, to wind banks and a floating, self-sufficient restaurant and garden! All these ideas are slowly shaping a collective vision of a city-environment that local residents deserve, all found inside their own creative power. This is how The People’s Island emerges within us—the public.

On the other hand, this project is a very tangible effort and has slowly moved from the realm of fiction to reality. Yes, that means that we’re making an island! Slowly but surely, The People’s Island is becoming a small floating platform composed of a series of rafts joined together (approx. dimensions 10ft x 10ft) made with indigenous materials like bamboo. The principle of The People's Island is to emerge as a temporary land-mass generated by people (literally) gathered together in a specific site, on firm land

In the past week, workshop participants worked collaboratively in shaping this new, fluid "land." Through fun, hands-on art

The first of these grants went to Katherine Maguad and Jeffrey Lazaro, who plan to utilize the knowledge and skills from local ceramic artists to create more hygienic stoves and efficient kitchen facilities. These sculptures/prototypes will be used in remote rural areas lacking from running water and electricity, and where children suffer malnutrition and health problems due to food contamination.

The second grant went to Aliana

The third grant went to Edmund Bacia and Peter Fantinalgo from the art collective, Binhi. Their idea is to produce a short video documentary around a song called “Hangin” (in English: Air), which was composed by Dina, a young artist from the underserved community of Banago. Dina passed away last year due to

And finally, the fourth grant was awarded to BALAYAN Organization, a group of environmentalists from La Salle University. Their plan is to use participatory art and experimental pedagogy to increasing community resilience to disasters in areas neighboring the ocean, which are the most vulnerable during the typhoon season.

As I write this, I prepare myself for a super busy but exciting week. We plan to celebrate Earth Day with a pre-launching of The People’s Island in the artificial lagoon in front of the local government building. Day after day, we encounter many challenges but also find creative solutions to keep the energy going, because

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.19.6" custom_padding="0px||" custom_margin="0px||"][et_pb_row admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.0.74" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

A week ago, I was just landing in Manila and getting ready to start the American Arts Incubator (AAI) program. Our first stop and "home-base" was Makati City, nowadays considered the Financial District of Manila and also an area that makes evident the booming market and financial growth of the country. There, I saw perhaps one of the biggest urban malls on the continent! Or, at least, one with enough room to exhibit a one of-a-kind, custom designed "Jeepney" for Pope Francis, or in colloquial terms here, “the Papamobil.” Anywhere else outside the perimeter of Makati City, one can see contrasting images of Filipino life, clearly demonstrating both the amazing opportunities and also the struggles present in this context. Our short stay in Manila also included a visit to Green-Papaya (a long standing artist-run space) and a quick look of Paul Pfeiffer’s new exhibition at MCAD.

Being my first time in the Philippines, I started to feel more confident navigating the local context on many levels: from public transportation to the lively social customs, and most importantly, the look and feel of the city. In this short time I have experienced an immediate connection with the country, perhaps because I spent many years living in South America, which, like the Philippines had a very strong influence from Spain (for at least 350 years) during Colonial times.

Three days later, Kate Spacek, ZERO1's program manager for AAI, and I were boarding an airplane to Bacolod in order to meet with Tanya Lopez and the staff from the Negros Museum, our host and local partner in the program. Our first two days with the museum were so carefully planned, which gave us the chance to meet local community leaders, journalists and representatives of the local government, literally one after the other. This system made me feel like sitting in a very professionally crafted “speed-dating” sort of situation. I’m not sure how common ‘speed-dating’ is in Filipino culture (ha ha) but given the precision and successful matching (of course, of professional interests), I think Tanya and her team found the perfect combination for initiating “first-sight” collaborations.

It has been only one week for us in the Philippines, but perhaps the most exciting part about this journey is to experience the energetic attitudes towards everyday life from the people of Bacolod. Their huge levels of inventiveness populate the city and create an environment where nothing seems impossible. From ingenious artifacts, like former military vehicles from WWII turned into (very) colorful public buses (or 'Jeepneys" in the local dialect); or bicycles and motorcycles attached to metal structures that are used to run food stands, transport merchandise or even replace taxis! Other unique occurrences that I have encountered by walking through the streets are as simple as an improvised hammock made only with two ropes, to entire homes made out of bamboo including the walls, flooring and even furniture.

Overall, the excitement and diligent work being done by our amazing team of museum staff and volunteers, plus the openness of the people from Bacolod make this place already feel like my home-away-from-home. Meeting after meeting, I feel ever more confident about the connections, understanding and support that we can gain in the next few weeks. Now that we’re moving into the thick of the project and workshops, it’s fascinating to see how the conversation naturally shifts. Instead of making more statements about what Art is, we’re all trying to figure out what Art can do for our local contexts…

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

From November 3rd to the 7th I had the incredible opportunity to visit ZERO1 in San Jose, California to meet with the team at ZERO1, the representative from the U.S. State Department, and the other three artists invited to the AAI program. I was coming from London, so even the change of vibe and the breeze of the Bay—instead of the cold Thames—was already a good promise for an energizing week.

The Orientation at ZERO1 was perhaps the most illuminating moment so far in this process of researching, ideating, and most importantly finding inspiration in whatever piece of news about the Philippines I could find for my project. So definitely, human contact and thoughtful conversations with peers are great rewards for working on this ambitious initiative, especially when you spend months prior to the meeting writing drafts, reading articles, preparing images, etc. with connections only being through the computer screen… But the good news is that amazing people were finally there to meet one another beyond the glossy surface of our laptops.

On day one, Kate Spacek (self-proclaimed Kickin' Kate in the ice breaker activity) welcomed the group with a huge smile and an agenda that looked so meticulously put together that it even included a time slot to walk around the block and stretch out! We moved through the agenda so quickly that just that first day was incredibly productive.

During day two, the group was a bit more relaxed and very productive conversations around the structure of the program, projects and proposed workshops started to emerge. For me, one of the highlights of this four-day meeting was a small session with Barbara Goldstein, an expert in Public Art and Board member at ZERO1. Barbara’s experience dealing with this kind of project was very evident even in the way she initiated conversation with us as the artists.

Barbara asked the artists to really consider what is the question that connects the pieces to this puzzle. This very question is the same that audiences always start with when looking or experiencing the artwork, and therefore invites them to engage with the artists’ intention. At the same time, with Barbara’s guidance, each artist analyzed the different interests and questions that were somehow less evident when thinking solo. Again, the question of “what is the question?” was the key for each of us to explore and plan more realistic ways to engage the communities we’ll be working with during the project.

Perhaps we all came to Orientation with more questions than certainties, which was absolutely productive. It was also good to be reminded that sometimes our role as artists isn’t just to provide completed ideas and products, or defined experiences. Instead, as artists, we can take the lead and explore creative ways of asking one another about the big and simple questions that surround our everyday spaces and our own communities which somehow remain unheard.

A tropical cyclone (Typhoon Kalmaegi) hit the north of the Philippines today, September 15th, 2014, causing floods and landslides, and killing several people. The list of catastrophic typhoons in the Philippines is huge, but still, perhaps one of the most destructive was the Haiyan (Yolanda) typhoon, which took place on November 3, 2013 and destroyed the city of Tacloban.

I’m lately absorbed by this intense history of meteorological disasters, all related to the unpredictable behavior of temperatures and atmospheric pressure in the Pacific Ocean. As time goes by, I’m more and more interested in understanding how Filipino culture develops in such a tense relationship with the natural environment.

In a way, it seems like the local community is being hunted by the surrounding ocean. A simple search on the Internet of the word Tacloban (epicenter of Typhoon Yolanda) still brings to the top of the list images of the tragedy. The destruction and violence of the typhoon are still spreading in the form of images, as if the storm were still propagating and the waters were high and muddy. However, it’s surprising how little information there is about other aspects of Tacloban’s life. The references I find on Tacloban only suggest loss and decay, but leave out any possible hint about the culture, social structure, or even energy of the city.

As I start this research, I’m finding inspiring references that soon will lead to an answer. Among the most fascinating examples are the Badjau, an indigenous ethnic group from South East Asia that is present in different areas of the Philippines. The Badjau live a seaborne lifestyle, using small hand-made boats to transport not only their people but also entire villages and supplies. This tribe was referred to as Sea-Gypsies for to their nomadic way of living. Their cosmology and rituals (from giving birth to celebrating funerals) encompass the oceanic world that sustains their society. However, due to constant attacks from modern pirates, territorial disputes, and religious confrontations with autonomous Muslim sects, some Badjau have been forced to temporarily settle in the most economically depressed areas of coastal cities, like Tacloban or Bacolod (Philippines), and therefore struggles with of a sort of reversed migration into stationary lives.

Meanwhile, unemployment and poverty in the Philippines are forcing other people to adapt to a similar kind of ‘unsettled’ way of living, which exists in a constant journey over defined trajectories, instead of set destinations. That is the case of the Pa-aling divers, fishermen who practice an extremely dangerous fishing style. Only connected to rubber tube that pumps oxygen into the lungs, multiple fishermen breath through a precarious diesel air compressor as they dive several feet into the ocean. They fish in international waters now, as the seas around the Philippines are already overfished. And because this all takes place on the 'high seas' (no man's land), there isn’t any person, government, or organization that can control this deadly practice.

I’m wondering: How could art practice and somewhat precarious survival ways of living coexist? Perhaps, one adapts to the other one, while creativity (or possibility) emerges within.