Last month wrapped up the ZERO1 American Arts Incubator in Gwangju, South Korea in partnership with the Gwangju Cultural Foundation. Gwangju is widely known as the site of the Gwangju Uprising (or May 18 Democratic Uprising), when the public responded to martial law instituted by the government, the closing of schools, and the banning of political activities with a large-scale civil uprising. The uprising began at Chonnam University with students protesting, and quickly spread with tens of thousands of protesters, hundreds of deaths, and thousands of injuries. This uprising paved the way for the democratization of South Korea in the late 1980s, and the event is a major part of South Korea’s history and is still extremely present for many in the country. Working in this very politically and socially engaged city, it was interesting to learn about the current issues of social inclusion that the participants were experiencing, that ranged from issues like processing trauma in the body to dealing with the complex relationship between younger and older members of society.

We began with a one week workshop, where we got to know one another, talk through the themes, and learn some new skills. My approach to the workshop was to use the concept of “home” as an entry point to the issue of social inclusion. “Home” is an idea we can all relate to—we have all felt at home at some point, whether it is a physical place, a group of people, or a mode of being, But what makes someone feel “at home” and what does it mean to belong in a space, community, or city? What might a future home look like, if we imagine one that is more inclusive?

Artist Joo Hong visited to talk about her social performances and interventions in Gwangju, around Korea, and in New York Times Square.

We tried to learn through action and our bodies. Participants brought objects that captured their feeling of home and improvised with them. Through these activities, we got used to the idea of creating space together, negotiating, and imagining. We were building a framework for ourselves.

We also visited Yangnim-Dong and thought about the meaning of doing this work in Gwangju today. We toured the beautiful Chinese Holy Tree (Horang Gasinaumu) Guest House and learned about the missionaries and religious and spiritual roots of the city that put a priority on caring for family, city, and justice. This felt very relevant to our themes of home and social inclusion.

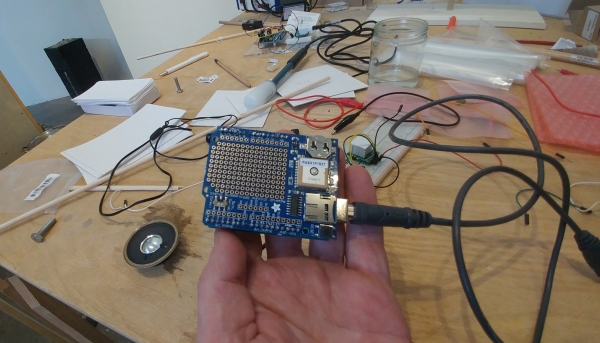

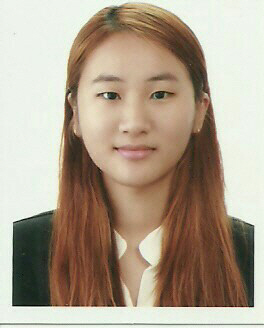

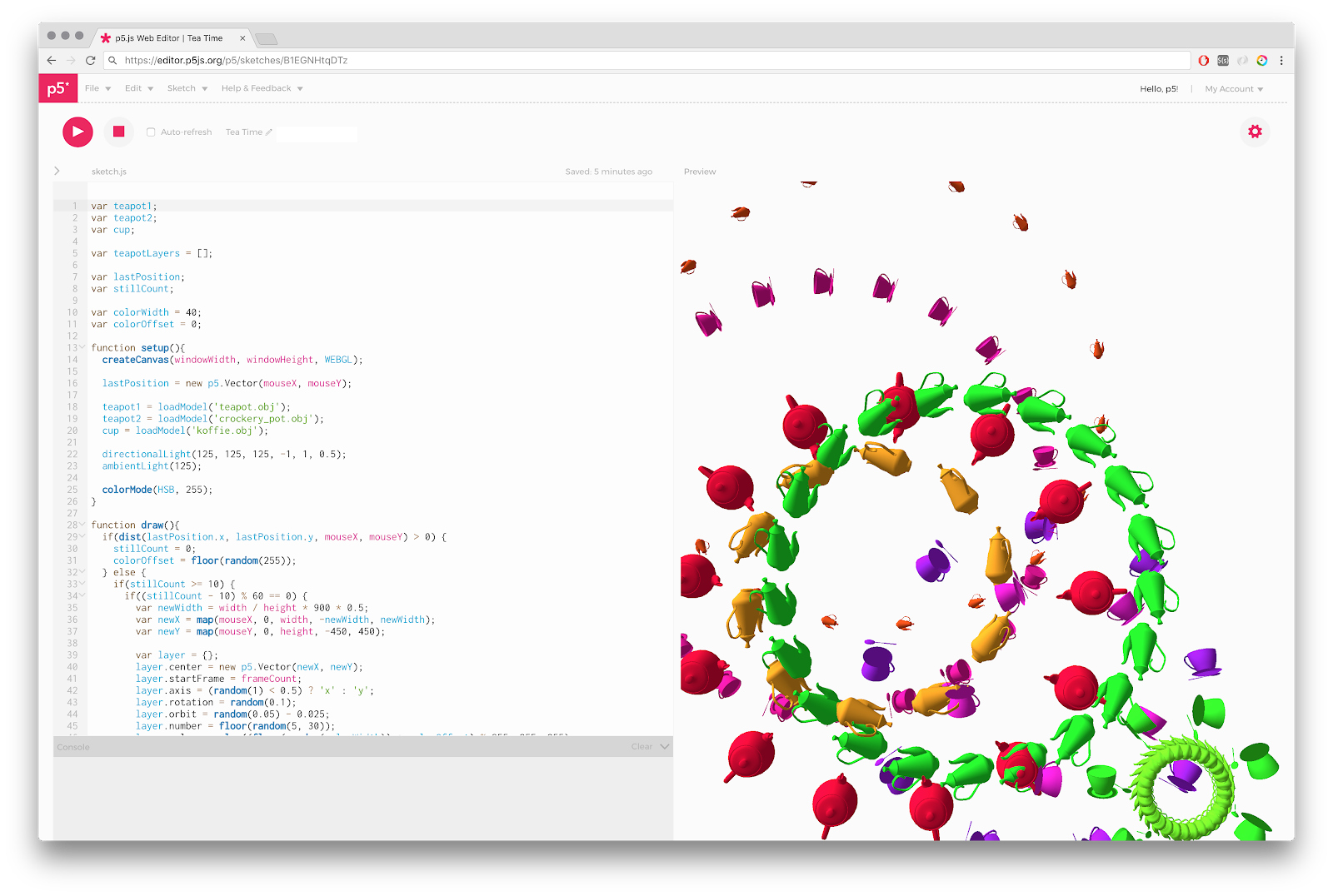

We also spent time learning technical skills to make the projects. We learned coding to create interactive drawings using p5.js. We used machine learning to train simple systems to recognize things like facial expressions, body positions, or basic objects. Then we thought about how to create interactive installations combining elements of camera input, projected content, and audience interaction.

After that busy week, we formed four teams and began developing team projects that would make up one bigger installation. The “Smarter Home” project reimagines smart homes of the future, trying to bring technology into personal space on our own terms. Each team selected an issue within the broader scope of social inclusion to address through a conversation room they created within the larger structure. They then developed one mode of interaction to use as the mechanic for their piece. This meant incorporating machine learning, audio processing, and computer vision techniques to track and respond to the presence of participants.

Nawon Paek, Taeguen Lim, Gaeyang Park, and Inhwa Yeom’s project III-iteracy raised awareness about illiteracy and the difficulty some people face in navigating the city. Creating an installation that reacted to eye blinks, they used coding techniques and visual effects as metaphors for understanding different experiences of seeing and reading.

Do Won Kim, Jung Suk Noh, Yun Jeong Kim, Ho Jong Jeong, and So Jeong Yun’s project took on imagined roles of family members to create their project I LOVE YOUt. Expanding on the traditional Korean pastime yutnori, they envisioned it as a means to communicate with family members and understand the history and spirit of Gwangju. It used machine learning to introduce a new game format that combines the past and the future by digitally linking analog games, and presenting the audience with image or text questions to share experiences from different moments in time. The experience drew on a shared sense of sorrow to form a community of hope.

Changwan Moon, Hyewon Kim, and JeongNang Choi’s project Feel-Fill investigated the way emotional pain is experienced in the body. After surveying local community members about their embodied pain, they created an interactive visualization that reacted to voice. When someone screamed in their room, a large portrait of the body would illuminate with mapped projections at the pain points.

Kitae Park, Minju Do, and Yonghyun Lim’s project How to Understand Your Daughter took on the smaller society known as the “family.” As they put it, “Home is a place where two different social roles collide: between what parents want their children to act like (as a member of the family) and what the children want to act and live like (as a member of a society).” In the middle of the installation is a diary by Minju, one of the team members, onto which a pre-recorded video of her day and her artworks are projected. The audience was invited to react to Minju’s day, experiencing it from her mother’s viewpoint, and respond using their bodies to two options: 1) I am worried about her future, 2) I am not worried about her future. The installation detected the bodily responses and visualized the broader community’s outlook on Minju’s future.

Together, the four works came together into one larger installation that offered our own “Smarter Home / 더 똑똑한 집.” A panel review and open house involving the public wrapped up everything up.

Earlier this month, we had the opportunity to stage a new iteration of this work as part of the International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) exhibition that will be held at the Asia Culture Center. The installation was developed significantly to adapt to a new site, audience, and ongoing goals of the participants.

This exchange taught me a lot about communication, which I think is at the core of feeling like you are home. As we navigated language differences, I found my definition of “understanding” expanding. I realized that though we may have different interpretations of what was being said, we could still find places to connect and build together. In some ways, it offered a wider, more forgiving and creative way of collaborating. Each of us were able to bring our individual realities into a loose framework that created something bigger.

I must say many thanks to Inhwa Yeom, our amazing production assistant, interpreter, and team member, the whole team at Gwangju Cultural Foundation, including Yong Soon, JinKyung Jeong, and Jinsil Choi, Shamsher Virk and Maya Holm who provided so much support from afar at ZERO1, the US Department of State for supporting this work, and all the participants who were so creative, committed, and generous with their energy.

Source: Jeonnam Daily (“Citizens have a direct say through 'New Media Art',” by Jin-sil Choi, May 29, 2019. Translated from Korean.)

It was a spring day in which the flowers were gradually beginning to fade after blooming. I had been tirelessly pursuing the expression of my story through a medium called new media art. The 2019 American Arts Incubator workshop, although brief, was an inspirational and exciting time. As a project coordinator, I know that the feeling was shared amongst all of the participants.

The workshop was organized by the US Department of State and ZERO1, leaders in Silicon Valley’s art and technology scene. The organizations have collaborated since 2015 to send US artists around the world and conduct workshops.

The Gwangju Cultural Foundation was chosen as the intermediary to help locals with diverse backgrounds access workshops. The program enabled participants to receive guidance from an experienced new media artist and professor at UCLA. Fifteen participants consisting of students, those new to artistic practices, and artists had the pleasure of expressing their ideas through the medium of new media art.

Even for participants with experience in the arts, the workshop posed the new challenge of expressing themselves in a third language, coding. However, the lead artist Lauren McCarthy, developed the p5.js software so that anyone could easily understand code. Thanks to the support allocated to each group, the participants became accustomed to the basic ideas, bit-by-bit. Despite the short amount of time and technological challenges, each group created their own artworks. With determination and a strong desire to learn, each team of participants was able to produce a meaningful piece that inspired audience members.

Because these artworks were produced by regular citizens, the pieces were relatable and accessible to the audience. One piece showed a family enjoying their national holiday together by playing Yut Nori, a traditional game. This work reminded viewers about the importance of cherishing family memories.

Another artwork that received praise depicted the tensions between a concerned mother and her 20-year-old daughter. Members of the audience were particularly drawn to, and impressed by, the interactive elements of this work. By incorporating projection mapping technology, the audience could make gestures that influenced the screen. This contributed to a meaningful experience, as each guest shared in the experience of expressing themselves through new media art.

This program demonstrated that new media art is able to express significant stories and ideas. More importantly, it illustrated that the creation of such content isn’t exclusive to experts and established artists, but to anyone who has feelings and opinions to express. This is in line with UNESCO Creative Network's educational values, aims, and objectives. Now there are ways in which people can create evocative and well produced works to express their stories. As a program, it illustrated a lot of possibilities in a short period of time, all while suggesting the direction of future media art.

If these local projects continue to develop and become established into our educational programs, it would be a great resource for citizens. I will do my best to support that development.

Source: Gwangju Daily News (“Do you think of 'media art' as a fresh concept?,” by Jeong Nang Choi, May 23, 2019. Translated from Korean.)

I recently had a special experience involving emerging media art. It was through the American Arts Incubator program, hosted by ZERO1 and the US Department of State. They collaborated with the US Embassy and Gwangju Cultural Foundation to carry out this unique month-long event. It was a workshop in which we discussed matters of societal impact such as social inclusion. As a group, we sought to express our thoughts on these issues through media art techniques.

Many people who have little-to-no experience in the arts, like myself, participated in this workshop because it welcomed ordinary people and artists alike. The artist who lead the workshop was Lauren McCarthy, a professor and researcher at UCLA. She began by delivering a presentation on a coding program that she designed called p5js. By entering data into this program, it enables the recognition of facial expressions, body positions, and objects.

After completing the basic coding course, the participants were divided into teams. Then the teams began to develop their projects in line with the social inclusion theme. They asked one another: “Is there a moment when I was marginalized or excluded?” They proceeded to dig into what the experience was, when it happened, and why. Following, they began a conversation about when they had a sense of belonging or being welcomed.

It was from these discussions that they reached a general consensus and began drawing up their team projects. Due to the diverse range of ages and life experiences among participants, ideas were in a lengthy state of back-and-forth debate. Lauren facilitated and helped to guide participants during the process.

After much intensive effort from the members, the four teams completed their art works. The first team created “Ill-Iteracy”: a system where analog and digital devices could successfully coexist. Team two made “I LOVE YOUt” which focused on restoring mutual understanding and respect between community members through the traditional Korean game, Yut Nori. The third team used surveys to ascertain how people felt and then created digital environments to overcome anxiety and emptiness in their piece “Feel-Fill”. The fourth team “How to Understand Your Daughter”, took on the task of finding unique perspectives on parent-child conflicts.

The four works were displayed for exhibition at Artspace 338 for about 10 days. The opening began with a briefing on each piece, presentations on the works, a panel review, and finally, audience questions that led to intense and in-depth discussions.

Through this workshop, I had the opportunity to meet emerging media artists who live in Gwangju and abroad. I felt pride and contentment in the fact that I was given the chance to collaborate with world-class artists and researchers. I also felt pride in being a part of Gwangju city, 'the pillar of innovative media art'.

The finished works will be displayed and presented again at a special exhibition in the 2019 International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) that will be held for a week at the Asian Culture Center. I hope that researchers, viewers, and artists alike will come to see what kind of emerging media art was produced.

Since January 2017, I have been attempting to become a human version of Amazon Alexa, a voice-activated AI system for people in their own homes. The project is called LAUREN. Anyone can visit get-lauren.com to sign up.

The process begins with an installation of a series of custom-networked devices that include cameras, microphones, switches, door locks, faucets, and other electronics. For three days, I remotely watch over the person 24/7 and control all aspects of their home. I attempt to be better than an AI, because I can understand them as a person and anticipate their needs.

LAUREN Testimonials, 2017. Directed by David Leonard.

This project represents one of the main themes of my practice, examining social relationships in the midst of surveillance, automation, and algorithmic living. In particular this past year, I’ve been focused on the concept of “home.” How do we know when we’re home, and how does technology fit into this feeling?

I’ve been investigating these questions through a series of projects. In 24h HOST, visitors take part in a small living room party that lasts for 24 hours, driven by artificial intelligence that automates the event and is embodied in a human HOST. Prior to the performance, guests register to attend via a website. Their online social identity is scraped and analyzed, and they are assigned an optimal time at which to arrive. Every five minutes throughout the party’s duration, one guest departs and a new guest arrives. I am the host.

Lauren McCarthy, 24h HOST, 2017. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann.

In The Changing Room, a custom software installation space invites participants to browse and select one of hundreds of emotions, then evoking that emotion in them and everyone in the space through a layered environment of light, visuals, sound, text, and interaction exhibited over the entire space. While it imagines a smart environment that controls feelings, the piece simultaneously invades and cares for the emotions of passersby.

Lauren McCarthy, The Changing Room, 2016. Photo by Kyle McDonald.

We are meant to think smart home devices are about utility, but the space they invade is personal. The home is the place where we are first watched over, first socialized, first cared for. How does it feel to have this role assumed by artificial intelligence? Our home is the first site of cultural education; it’s where we learn to be a person. By allowing these devices in, we outsource the formation of our identity to a virtual assistant whose values are programmed by a small, homogenous group of developers.

I’m looking forward to bringing these research themes to Gwangju, South Korea next month as part of the American Arts Incubator. Working with a group of twenty local participants, we will tackle the issue of social inclusion. Nearly 96% of South Koreans identify as ethnically Korean, which provides a unique challenge to addressing inclusion, and is just one challenge in the broader picture of diversity. Other aspects we will consider include disability, gender roles, and identity in the context of the May 18 1980 Democratic Uprising that began in Gwangju.

It’s obviously tricky to come into a place as a visitor and try to talk about social inclusion and identity. So I am planning to do a lot of listening and learning. As a starting point, we will use the concept of “home.” Home is an idea we can all relate to—we have all felt at home at some point, whether it is a physical place, a group of people, or a mode of being. But what makes someone feel “at home” and what does it mean to belong in a space, community, or city? What might a future home look like, if we imagine one that is more inclusive?

We will create an interactive installation driven by machine learning that represents our group vision of a future smart home. Rather than imposing values and protocols, this home will aim to create inclusive spaces for open conversation and freedom of expression. We will also visit some “homes” around the city of Gwangju, and challenge our ideas of what form and place home needs to occupy. To build the installation, we’ll be using a tool called p5.js, which is designed to “sketch with code” and learn coding through making art.

p5.js Web Editor. Photo by Lauren McCarthy.

For this month-long project, I’m partnering with the Gwangju Cultural Foundation. They are an organization that is very tied into the local culture and arts, and they’ve been extremely helpful as we prepare for the workshop and incubator.

Gwangju Cultural Foundation workshop space. Photo courtesy of Gwangju Cultural Foundation.

I’m looking forward to getting on the ground and learning all I can. If you’d like to follow along, you can join our Facebook group. We’ll have an open house at the end of the exchange, where the final installation and team projects will be on display from May 10-11, 2019.