[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.0.47" custom_padding="0|0px|29.4844px|0px|false|false"][et_pb_row custom_padding="0|0px|14.7344px|0px|false|false" admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.19.6" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

Today is my last day in the Philippines. A few hours ago I landed in Manila, after waiting for over an hour while the Presidential airplane was landing at the Bacolod airport. I was already installed in my airplane seat, all buckled-up, and through the tiny

After all the anticipation, President Benigno Noynoy Aquino III was descending from his airplane and everyone around -even inside my airplane- suddenly stood up while a small marching band played quietly the national anthem in the background. This moment was perhaps the best closure for my time in Bacolod, also the moment when I finally understood something essential about Filipino culture: This is a place bound together by very strong community values. A strong sense of togetherness, a shared identity, and most importantly, an admirable resilience to an adverse history (colonialism, natural disasters, inequality) rule this country. I couldn’t be luckier for the opportunity to work in such an energizing context like Bacolod City, where art and community engagement come hand-in-hand.

Shortly after I landed in Manila, I had a three-hour taxi ride through the city’s heavy traffic, even though I was traveling only 7 miles. I was heading to Green Papaya Projects, a well established independent art space that has been active for over a decade and run by amazing people (Pewee and Merv). They had invited me to give an informal presentation about my recent work in Bacolod and “The People’s Island” project. You can imagine, I was both excited to share the experience and very fresh documentation but also quite nervous since it was only five days after the public launching of the project and I was still processing the intense experience...

So, after a public lecture at the Negros Museum addressing the role of Public Art in fostering community participation and healthy environments; a five-day workshop exploring collaboration; sustainable urban planning and socially engaged art, I invited participants to creatively explore their city as an extension of the endangered natural world. This is how The People’s Island became a thinking tool, a collective dream and an immersive artistic experience that engaged around 150 people through a public event and exhibition.

Framed as a large participatory art project, The People’s Island really took place in the public sphere of Bacolod: in urban spaces, natural sites and even in our collective consciousness. The project evolved slowly during three weeks of intense work, conversations

Thus, on April 25th at

Once the public arrived

Around

Around

Around

*Its next destination will be Suyac Island in the Northern part of the Negros region, where the structure will re-emerge as the Floating Eco-Resource Center and Library.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.0.47" custom_padding="0|0px|29.4844px|0px|false|false"][et_pb_row admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.19.6" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

It’s a hot Saturday afternoon and I feel my voice resonate strongly inside my chest while my hearing still recovers from the pressurized cabin of the airplane. I can even hear an echo leaking through the century-old walls of the Negros Museum in Bacolod… Well, the fact is that I’m

This was just our third day in the city and my brain was already full of ideas, questions, and yes, lots and LOTS of new names to remember. Just the night before, I gave a public lecture in the same room, which created a lot of curiosity among local artists, environmentalists

During the same talk, I introduced the public art project that I will develop in Bacolod titled, The People’s Island, which revolves around the idea that “reality is none other but the things we do together.” On the one hand, The People’s Island is a metaphorical site, or perhaps a thinking tool that allows workshop participants to create a fictional place that responds to their visions of what their ideal city or environment could look like. Throughout the workshops, participants gathered their concerns about environmental health and re-enacted them through quick, stop-motion animations. They then designed 3D scaled models of a fictive city, as a means to propose sustainable urban planning. This was achieved by transforming small paper sculptures into plans for hybrid objects that use clean energy and have a public function—from street planters that collect solar energy and emit light at night that replace expensive street lighting, to wind banks and a floating, self-sufficient restaurant and garden! All these ideas are slowly shaping a collective vision of a city-environment that local residents deserve, all found inside their own creative power. This is how The People’s Island emerges within us—the public.

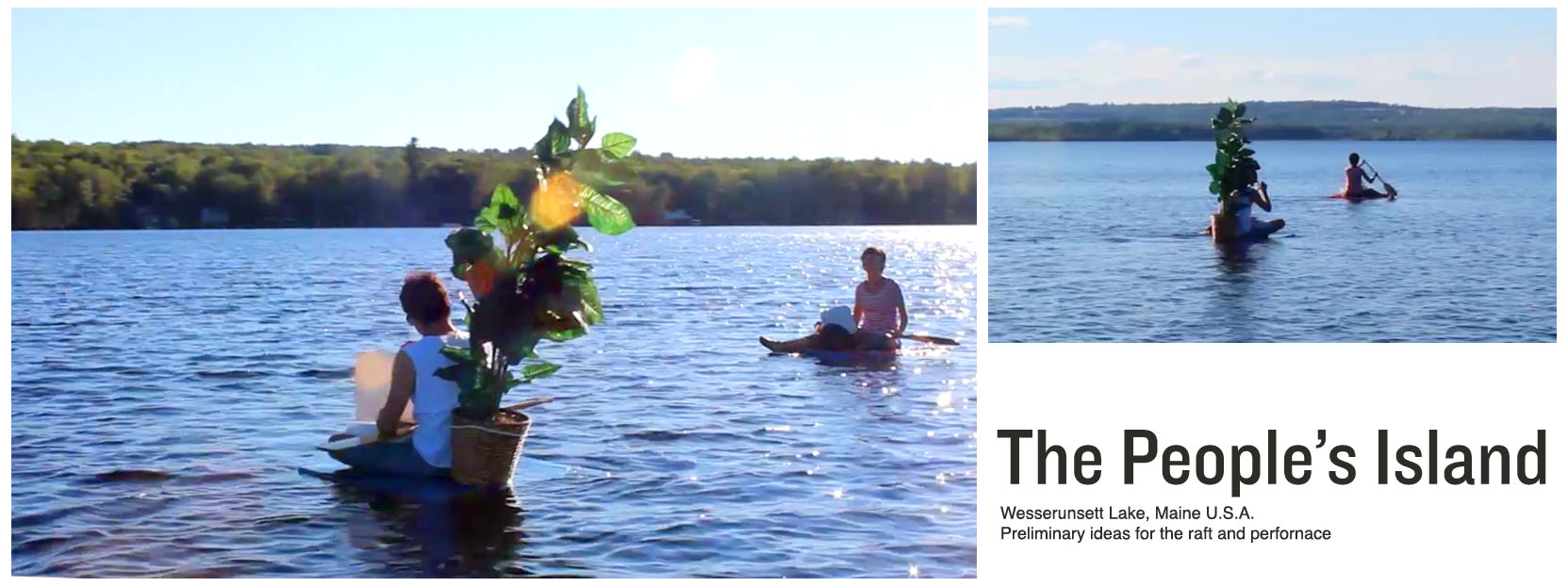

On the other hand, this project is a very tangible effort and has slowly moved from the realm of fiction to reality. Yes, that means that we’re making an island! Slowly but surely, The People’s Island is becoming a small floating platform composed of a series of rafts joined together (approx. dimensions 10ft x 10ft) made with indigenous materials like bamboo. The principle of The People's Island is to emerge as a temporary land-mass generated by people (literally) gathered together in a specific site, on firm land

In the past week, workshop participants worked collaboratively in shaping this new, fluid "land." Through fun, hands-on art

The first of these grants went to Katherine Maguad and Jeffrey Lazaro, who plan to utilize the knowledge and skills from local ceramic artists to create more hygienic stoves and efficient kitchen facilities. These sculptures/prototypes will be used in remote rural areas lacking from running water and electricity, and where children suffer malnutrition and health problems due to food contamination.

The second grant went to Aliana

The third grant went to Edmund Bacia and Peter Fantinalgo from the art collective, Binhi. Their idea is to produce a short video documentary around a song called “Hangin” (in English: Air), which was composed by Dina, a young artist from the underserved community of Banago. Dina passed away last year due to

And finally, the fourth grant was awarded to BALAYAN Organization, a group of environmentalists from La Salle University. Their plan is to use participatory art and experimental pedagogy to increasing community resilience to disasters in areas neighboring the ocean, which are the most vulnerable during the typhoon season.

As I write this, I prepare myself for a super busy but exciting week. We plan to celebrate Earth Day with a pre-launching of The People’s Island in the artificial lagoon in front of the local government building. Day after day, we encounter many challenges but also find creative solutions to keep the energy going, because

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="3.19.6" custom_padding="0px||" custom_margin="0px||"][et_pb_row admin_label="row" _builder_version="3.0.48" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="3.0.47" parallax="off" parallax_method="on"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="3.0.74" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat"]

A week ago, I was just landing in Manila and getting ready to start the American Arts Incubator (AAI) program. Our first stop and "home-base" was Makati City, nowadays considered the Financial District of Manila and also an area that makes evident the booming market and financial growth of the country. There, I saw perhaps one of the biggest urban malls on the continent! Or, at least, one with enough room to exhibit a one of-a-kind, custom designed "Jeepney" for Pope Francis, or in colloquial terms here, “the Papamobil.” Anywhere else outside the perimeter of Makati City, one can see contrasting images of Filipino life, clearly demonstrating both the amazing opportunities and also the struggles present in this context. Our short stay in Manila also included a visit to Green-Papaya (a long standing artist-run space) and a quick look of Paul Pfeiffer’s new exhibition at MCAD.

Being my first time in the Philippines, I started to feel more confident navigating the local context on many levels: from public transportation to the lively social customs, and most importantly, the look and feel of the city. In this short time I have experienced an immediate connection with the country, perhaps because I spent many years living in South America, which, like the Philippines had a very strong influence from Spain (for at least 350 years) during Colonial times.

Three days later, Kate Spacek, ZERO1's program manager for AAI, and I were boarding an airplane to Bacolod in order to meet with Tanya Lopez and the staff from the Negros Museum, our host and local partner in the program. Our first two days with the museum were so carefully planned, which gave us the chance to meet local community leaders, journalists and representatives of the local government, literally one after the other. This system made me feel like sitting in a very professionally crafted “speed-dating” sort of situation. I’m not sure how common ‘speed-dating’ is in Filipino culture (ha ha) but given the precision and successful matching (of course, of professional interests), I think Tanya and her team found the perfect combination for initiating “first-sight” collaborations.

It has been only one week for us in the Philippines, but perhaps the most exciting part about this journey is to experience the energetic attitudes towards everyday life from the people of Bacolod. Their huge levels of inventiveness populate the city and create an environment where nothing seems impossible. From ingenious artifacts, like former military vehicles from WWII turned into (very) colorful public buses (or 'Jeepneys" in the local dialect); or bicycles and motorcycles attached to metal structures that are used to run food stands, transport merchandise or even replace taxis! Other unique occurrences that I have encountered by walking through the streets are as simple as an improvised hammock made only with two ropes, to entire homes made out of bamboo including the walls, flooring and even furniture.

Overall, the excitement and diligent work being done by our amazing team of museum staff and volunteers, plus the openness of the people from Bacolod make this place already feel like my home-away-from-home. Meeting after meeting, I feel ever more confident about the connections, understanding and support that we can gain in the next few weeks. Now that we’re moving into the thick of the project and workshops, it’s fascinating to see how the conversation naturally shifts. Instead of making more statements about what Art is, we’re all trying to figure out what Art can do for our local contexts…

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

From November 3rd to the 7th I had the incredible opportunity to visit ZERO1 in San Jose, California to meet with the team at ZERO1, the representative from the U.S. State Department, and the other three artists invited to the AAI program. I was coming from London, so even the change of vibe and the breeze of the Bay—instead of the cold Thames—was already a good promise for an energizing week.

The Orientation at ZERO1 was perhaps the most illuminating moment so far in this process of researching, ideating, and most importantly finding inspiration in whatever piece of news about the Philippines I could find for my project. So definitely, human contact and thoughtful conversations with peers are great rewards for working on this ambitious initiative, especially when you spend months prior to the meeting writing drafts, reading articles, preparing images, etc. with connections only being through the computer screen… But the good news is that amazing people were finally there to meet one another beyond the glossy surface of our laptops.

On day one, Kate Spacek (self-proclaimed Kickin' Kate in the ice breaker activity) welcomed the group with a huge smile and an agenda that looked so meticulously put together that it even included a time slot to walk around the block and stretch out! We moved through the agenda so quickly that just that first day was incredibly productive.

During day two, the group was a bit more relaxed and very productive conversations around the structure of the program, projects and proposed workshops started to emerge. For me, one of the highlights of this four-day meeting was a small session with Barbara Goldstein, an expert in Public Art and Board member at ZERO1. Barbara’s experience dealing with this kind of project was very evident even in the way she initiated conversation with us as the artists.

Barbara asked the artists to really consider what is the question that connects the pieces to this puzzle. This very question is the same that audiences always start with when looking or experiencing the artwork, and therefore invites them to engage with the artists’ intention. At the same time, with Barbara’s guidance, each artist analyzed the different interests and questions that were somehow less evident when thinking solo. Again, the question of “what is the question?” was the key for each of us to explore and plan more realistic ways to engage the communities we’ll be working with during the project.

Perhaps we all came to Orientation with more questions than certainties, which was absolutely productive. It was also good to be reminded that sometimes our role as artists isn’t just to provide completed ideas and products, or defined experiences. Instead, as artists, we can take the lead and explore creative ways of asking one another about the big and simple questions that surround our everyday spaces and our own communities which somehow remain unheard.

A tropical cyclone (Typhoon Kalmaegi) hit the north of the Philippines today, September 15th, 2014, causing floods and landslides, and killing several people. The list of catastrophic typhoons in the Philippines is huge, but still, perhaps one of the most destructive was the Haiyan (Yolanda) typhoon, which took place on November 3, 2013 and destroyed the city of Tacloban.

I’m lately absorbed by this intense history of meteorological disasters, all related to the unpredictable behavior of temperatures and atmospheric pressure in the Pacific Ocean. As time goes by, I’m more and more interested in understanding how Filipino culture develops in such a tense relationship with the natural environment.

In a way, it seems like the local community is being hunted by the surrounding ocean. A simple search on the Internet of the word Tacloban (epicenter of Typhoon Yolanda) still brings to the top of the list images of the tragedy. The destruction and violence of the typhoon are still spreading in the form of images, as if the storm were still propagating and the waters were high and muddy. However, it’s surprising how little information there is about other aspects of Tacloban’s life. The references I find on Tacloban only suggest loss and decay, but leave out any possible hint about the culture, social structure, or even energy of the city.

As I start this research, I’m finding inspiring references that soon will lead to an answer. Among the most fascinating examples are the Badjau, an indigenous ethnic group from South East Asia that is present in different areas of the Philippines. The Badjau live a seaborne lifestyle, using small hand-made boats to transport not only their people but also entire villages and supplies. This tribe was referred to as Sea-Gypsies for to their nomadic way of living. Their cosmology and rituals (from giving birth to celebrating funerals) encompass the oceanic world that sustains their society. However, due to constant attacks from modern pirates, territorial disputes, and religious confrontations with autonomous Muslim sects, some Badjau have been forced to temporarily settle in the most economically depressed areas of coastal cities, like Tacloban or Bacolod (Philippines), and therefore struggles with of a sort of reversed migration into stationary lives.

Meanwhile, unemployment and poverty in the Philippines are forcing other people to adapt to a similar kind of ‘unsettled’ way of living, which exists in a constant journey over defined trajectories, instead of set destinations. That is the case of the Pa-aling divers, fishermen who practice an extremely dangerous fishing style. Only connected to rubber tube that pumps oxygen into the lungs, multiple fishermen breath through a precarious diesel air compressor as they dive several feet into the ocean. They fish in international waters now, as the seas around the Philippines are already overfished. And because this all takes place on the 'high seas' (no man's land), there isn’t any person, government, or organization that can control this deadly practice.

I’m wondering: How could art practice and somewhat precarious survival ways of living coexist? Perhaps, one adapts to the other one, while creativity (or possibility) emerges within.